1. Introduction

How might a military move from framing warfare and change in such incremental, pragmatic, problem-solution and other Newtonian styled modes of conceptualisation? Design theorists have for much of the twentieth century, and largely outside military forces, positioned the fantastic and divergent modes of thinking as the primary cognitive space to begin any discussions on the future. Modern militaries must confront their own war ontologies in that complex reality will not permit highly efficient, static ‘problem-solution’ constructs to last very long, if at all.

Novelty, improvisation, experimentation and ‘creative destruction’ must be integrated into any war paradigm so that transformation is welcomed, regardless of what sacred cows must be led to slaughter. Designer and complexity theorist Dorst explains:

The core paradox of innovation management lies in the fact that the ideal image of an organization still is that of a well-oiled machine where efficiency reigns supreme. The need to create novelty is at odds with this model, as novelty inevitably disturbs existing processes and might be accompanied by ‘creative destruction’. How do we find a balance between routine operation and the need for novelty and change in an organization? To answer this question, the field of innovation management has had to become a hybrid: it combines a rich mix of subjects in policy-making, strategy formulation, organizational structures, and management styles with elements of design theory … and fundamental analyses of the notion of innovation itself. Combined, these create a context for thinking about innovation within organizations (Dorst, 2015, p. 143).

This paper is part four of a four-part series. The first part provided a broad introduction of how and why militaries stifle new ideas and consider the pattern of outright rejection of novelty and punishment of unorthodox thinking in war (Zweibelson, 2024c). The second part discussed innovation through the lens of military forces and war paradigms to understand how militaries are mostly inhibitive of innovation especially in new and emerging warfighting domains (Zweibelson, 2024b). The third part discussed how institutions perpetuate concepts into irrelevance (Zweibelson, 2024a). In this final offering, I challenge traditional military thinking by advocating for a paradigm shift. I argue that militaries must abandon Newtonian incremental, pragmatic approaches that are based in the known war paradigms and instead embrace innovation through creative destruction and the fantastic.

2. Modern militaries: pragmatic and formulaic

Modern militaries fixate on preconceived objectives and goals despite acknowledging that complex reality, particularly the chaotic and emergent characteristics of war, restrict such actions to temporary, localised and proximate opportunities. Western society, based upon ancient Greek philosophies concerning the natural world, order an individual’s heroic actions that accomplish the desired and predicted change in the world. Future goals and objectives first are rendered in the same pragmatic rationalisation provided earlier and reinforced in how institutional defenders will seek to extend the past constructs cherished and endorsed by the institution into tomorrow’s uncertainty rather than innovate toward a novelty that destroys these beliefs and institutionally sanctioned ideas. Stanley and Lehman clarify this with:

Though often unspoken, a common assumption is that the very act of setting an objective creates possibility. The very fact that you put your mind to it is what makes it possible. And once you create the possibility, it’s only a matter of dedication and perseverance before you succeed. This can-do philosophy reflects how deeply optimistic we are about objectives in our [Western, modern] culture. All of us are taught that hard work and dedication pay off – if you have a clear objective.

… Objectives might sometimes provide meaning or direction, but they also limit our freedom and become straitjackets around our desire to explore. After all, when everything we do is measured against its contribution to achieving one objective or another, it robs us of the chance for playful discovery. So objectives do come with a cost. Considering that cost is rarely discussed in any detail (Stanley & Lehman, 2015, pp. 2–3).

The Western, scientific-inspired, factory-engineered mode of moving pragmatically and incrementally through complex reality does not lead to military innovation except those discoveries that were so close to being realised, normal decision-making and managerial analysis would undoubtedly have run into them eventually (Stanley & Lehman, 2015, pp. 34–38). For consequential innovation, organisations must abandon the fixation on pragmatic thinking and adherence to routinised policy making or strategic formulation. Instead, they need to understand and appreciate how innovation requires a creative leap. Horst Rittel explains that creative leaps are ‘something indescribable and beyond reason, but nevertheless indispensable and important’ (Protzen & Harris, 2010, p. 123). Such ideation and exploration occur in the fantastic, where fantasy and imagination are exceptional, disruptive and likely unsettling to the institutional defenders. Creativity is subsequently ill defined and deemed unscientific in that militaries position it with ‘military artistry’ rather than any scientific logic or foundational principles for warfare. Creativity ‘is an island of mystery on a sea of irrationality, even for devoted navigators on the waters’ (Protzen & Harris, 2010, p. 123).

3. Models: innovation begins with the fantastic

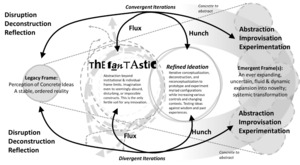

Innovation begins not in the pragmatically framed and historically measured, but the fantastically vivid and wildly unknown, as first presented in Part 1 of this series (Zweibelson, 2024c). Figure 1 provides one model for how innovation occurs within organisations to include military ones and is applied specifically for war in this treatment. However, the flow of ideas, experimentation, implementation and reflective practice is how any creative act might unfold, whether one is fighting an adversary, creating a new song, or devising a new restaurant kitchen configuration. Figure 1 is a model, and all models are flawed abstractions and simplifications of what is a complex reality impossible to capture in one or all possible models. Models are, according to Daft and Weick (1984), ‘a somewhat arbitrary interpretation imposed on organized activity. Any model involves trade-offs and unavoidable weaknesses’ (Daft & Weick, 1984). They can only offer a sliver of complex reality, and whether that glimpse is useful or not remains an ever-changing target of opportunity and risk for humans seeking stability, control and prediction in a world where rarely such advantages are clear or realised (Gharajedaghi, 2011, p. 26). Models are also only part of what constitutes a paradigm or socially constructed frame for how humans make sense of reality.

We use models to connect conceptual theories about how the world functions, and consider how the relationship between theoretical processes work when represented within a model and enacted through methods upon the external world (Jaynes, 2000, p. 53). For example, the cardiovascular community for decades applied medical theories and paired them to a ‘heart is a pump’ model. Yet in the 1990s, a small movement broke from this and replaced the pump model with that of a ‘sponge’ which would later usher in new treatment techniques and methods that reinforced some theories while encouraging the development of alternatives. Conversely, flawed theories can be tossed out but their original models might remain. Physicist Niels Bohr’s theory on atomic structure would later be disproven and replaced by advanced theories, yet his original model that atomic structures operate ‘like the solar system’ remained. As Jaynes explains: ‘A model is neither true nor false; only the theory of its similarity to what it represents’ (Jaynes, 2000, p. 53). Figure 1 thus offers a theory of innovation for how humans change their world and their understanding of reality.

Fantastical thinking begins in abstraction, beyond any prescribed individual or institutional limits. This requires social paradigm awareness so that one can question why certain things or ideas are acceptable, while others are either unacceptable or deemed irrational or even impossible (Sheldon & Gray, 2011). Fantastical thinking also requires a curiosity capable of conceptualising beyond institutional limits once those barriers are realised and probed with ‘why-centric’ questions. Thinking that pushes beyond institutional barriers ascends to the level of philosophy, and requires social paradigm recognition and beyond that, the anticipation of paradigm shifting from one social paradigm to another.[1] Yet how one thinks logically throughout the innovative cycle requires further explanation.

Fantastical thinking requires abductive logic rather than the more familiar inductive or deductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning starts with generalised statements or rules, and correlates them to specific contexts, such as how Sherlock Holmes might deduce a criminal is left-handed by the shoe prints left at the scene; all left-handed people is the general, this unknown criminal is the particular. Mrazek critiques modern militaries that show excessive adherence to principles, rules and maxims where a favourite one ‘is pulled out of the bag to suit each victory or, when the standard units of measure do not quickly or easily fit the circumstances, cliches such as “bold stroke of genius” or “brilliant intellect” are offered’ (Mrazek, 1968, p. 14). Deductive reasoning in military applications is a race to form the most cohesive and universal of lists and measurements, so that once the patterns are captured, one need only consult the doctrine and pair the emerging challenge with established ‘problem-solution’ relationships. When this leads to victory, it validates further investment in deductive reasoning for war. When failure occurs, the institution is apt to blame ‘operator error’ and seek repeating the process and changing out the operator so that the desired solution is accomplished. This logic largely governs our modern training centres to this day (Zweibelson, 2014).

Aside from deductive reasoning, modern militaries do pursue a sort of pseudo-scientific mimicry of the natural sciences where some inductive reasoning is applied, while still grounded upon unscientific beliefs, behaviours and processes (Paparone, 2017; Zweibelson, 2023d, pp. 77–80). Inductive reasoning builds generalised conclusions based on specific contexts that operate in a particular hypothesis. If a person watches the weather report and a large storm is approaching, they may select to drive home earlier to avoid traffic delays; individual driving is particular, the historic pattern of stormy weather causing traffic delays is a generalised conclusion. Inductive and deductive reasoning operate within a premeditated configuration of hypotheses and proposed relationships whether general to specific, or specific to general.

Abductive reasoning differs. Abductive reasoning operates by forming and evaluating different hypotheses within a complex, dynamic reality where information is incomplete, puzzling, does not comply with inductive or deductive logics, or is transforming within an emergent system as one engages within it (Tsoukas, 2009; Weick, 2006a). Inductive and deductive reasoning seek to apply general rules, while abductive reasoning works abstractly to find relationships that are systemic or systematic and often form novel configurations not previously considered or known. Analytic reasoning pairs known solutions to new problems that seem from the onset to suggest some correlation, while abductive thinking transforms a system, dissolving the current problem while introducing entirely emergent ones in that act of innovation with systemic consequences (Ackoff, 1981; Detrick, 2002).[2] Abductive reasoning involves improvisation, which is oppositional to any premeditated or predetermined logical arrangements. Improvisation ‘deals with the unforeseen, it works without a prior stipulation, it works with the unexpected’ (Weick, 1998). Strategic formation rendered in deductive or inductive logics largely subscribe to some version of an ‘ends-ways-means’ ordering of reality where future preconceived ends rationally link to analytically optimised ways and means (Paparone, 2013). Strategic innovation does not function this way, except in incremental modes of building upon existing legacy frame constructs in support of the dominant war paradigm and institutionalised identity.

Abduction disrupts the foundations for planning, and thus any pre-established goals and the ‘ends-ways-means’ configuration originally devised by ancient Greek natural philosophers.[3] Abductive reasoning is most applicable to complexity where emergence unfolds in nonlinear and novel, unpredictable ways. Complex systems function where the only constant is change, and abductive logic must move improvisationally through novel experimentation and ideation unbounded by legacy limitations or predetermined goal formation. Chia and Rasche expand on this: ‘strategy making [concerning disruptive innovation] is largely improvisational; strategy slowly emerges through the internalised predispositions that actors refer to … strategy making does not simply take place in boardrooms’ (Chia & Rasche, 2022). An incremental or evolutionary mode of strategic progress enacts the modern military paradigm, yet it does not encompass complex reality nor consider beyond these paradigmatic limits. Alternative paradigms provide vast areas for innovating strategies otherwise unreachable and unimaginable using this systematic, sequential and narrow approach that shuns the fantastic in favour of the pragmatic.

The fantastic is the infinity of human abstraction, where every possible idea may inhabit a void that is otherwise ignored or unimagined. In ancient Chinese philosophy, this appears consistent with the functional emptiness that is the ‘latent background to all things – in the sense that one speaks of the background to a painting or a background of silence: that background constitutes a stock from which sound is produced and that makes that sound resonate, the stock from which a brush stroke emerges and thanks to which it can vibrate’ (Jullien, 2004, p. 110). The fantastic is where multiple social paradigms interact, overlap or tangle into tensions and contradictions, yet also where a reflective practitioner might realise unimagined opportunities through shifting between paradigms and exploring the otherwise ignored (Gioia & Pitre, 1990; Lewis & Grimes, 1999; Lewis & Kelemen, 2002; Schultz & Hatch, 1996). Improvisational thinking and abductive logic charter this journey that quickly spill out of one paradigm into others, and back and forth. Complexity theorist Gharajedaghi (2011) provides a useful summary of paradigm shifting that occurs in this initial exploration into the fantastic:

A shift of paradigm can happen purposefully by an active process of learning and unlearning. It is more common that it is a reaction to frustration produced by a march of events that nullify conventional wisdom. Faced with a series of contradictions that can no longer be ignored or denied and/or an increasing number of dilemmas for which prevailing mental models can no longer provide convincing explanations, most people accept that the prevailing paradigm has ceased to be valid and that it has exhausted its potential capacity (Gharajedaghi, 2011, p. 8).

Gharajedaghi is addressing scientific paradigms in the above passage due to his point that one paradigm is prevailing, and another has additional potential capacity the invalidated one lacks. Kuhn’s original premise of scientific paradigms is where this original ‘paradigm shift’ was conceptualised first, while social paradigm theory would develop later (Kuhn, 1996). Social paradigms, which encompass all possible human framings of war and warfare, can have paradigm shifts where a legacy or insufficient war paradigm is discarded in a cognitive shift to another one, or there can also be shifting between competing or incompatible war paradigms that remain operationalised by different groups within a conflict (Gioia & Pitre, 1990; Lewis & Grimes, 1999; Schultz & Hatch, 1996).[4] For example, the modern Chinese war paradigm (that of a Sino-Marxist modern communist philosophy integrated with ancient Chinese philosophical influences) is maintained by Chinese political leadership and most of their military apparatus, while Western democracies engage within a Westphalian, Clausewitzian, Newtonian war paradigm. While China incorporates many Western theories, models and methodologies for warfare, we tend to completely misinterpret this by framing their war paradigm in our own familiar framework of values and beliefs. This prevents us from realising the limits of our own paradigm and rendering us blind to the fact that what comes next will be unlike anything we are familiar with.

Refined ideation occurs as operators move from the fantastic into iterations of improvisation and experimentation, whether conceptual or using artefacts in controlled settings to test out potential outcomes.[5] These efforts require iterations in that conducting single event, isolated or highly scripted scenarios will only produce performance outcomes that are limited to the rigid testing conditions designed by the evaluators. Returning to the U.S. Navy and Mitchell’s ambition to prove an emerging vulnerability to battleships as discussed previously (Zweibelson, 2024a), the naval exercise controllers sought to limit his experiment in ways that they felt could marginalise or eliminate any unwanted test results. In refined ideation, a reflective practitioner already understands their dominant war paradigm and when the institution may attempt to restrict or limit any refined ideation so that cherished beliefs are not confronted. It is in this overlap of what is known to exist and what is currently unfolding in a surprising, uncertain reality where the reflective practitioner seeks to ‘sense-make’ and refine their ideation by testing new ideas against the system that includes institutional frameworks and beliefs (Tsoukas, 2009).

4. Converging and diverging: improvisation through hunch and flux

Operators move from the fantastic to the refinement of ideation iteratively, where thinking fantastically can lead to what sociologists such as Weick (2011), Perin (2005) and Locke et al. (2008) term ‘hunch’. The hunch can be similar to how we use words such as ‘concept’ and ‘conjecture’. Weick explains hunches with ‘hunches … [are] an undifferentiated sense of something, as well as doubt shadowed by discovery. Hunches resemble poetic discourse that reconstitutes absent events’ (Weick, 2011). For Weick, a hunch is temporary and highlights the provisional nature of concepts and ‘the fact that they are substantial abridgements of perceptual reality’ (Weick, 2011). Hunches form in the fantastic, also termed ‘flux’ by Weick where the vastness of human conceptualisation is infinite and ever-changing, in some Shakespearian ‘airy nothing’ that begins to materialise temporarily and as this occurs, new things are named. Yet ‘names that identify objects forever do not’ in how flux flows and manifests (Weick, 2011). The iteration between the fantastic (flux) and new hunches (refined ideation) is that, during this unfolding, nonlinear journey, ‘people have a chance to redo their hunches, substitutions and interpretations’ (Weick, 2011).

Most counterintuitively to those accustomed to the ancient Greek logic of progressing from abstraction toward concrete, decisive action, Weick’s framing of sensemaking in complexity and Donald Schön’s complementary ‘reflective practice’ move in opposition, connecting hunches back to flux to practice generative doubt (Ferry & Ross-Gordon, 1998; Schön, 1984; Visser, 2010). They insist that what might appear the most concrete is actually likely to be the most abstract, and the opposite also true (Weick, 2011). One of the ways humans socially construct a rich, complex reality upon the existing naturally multifaceted world consists of a shifting from thinking in a perceptually based, active exploration of reality to that of a categorically based knowing, which seeks enhanced coordination and convergence (Hatch & Yanow, 2003; Putnam, 1983; Putnam & Pacanowsky, 1983). In other words, as soon as we might establish a hunch in the ever-shifting flux, we seek to rigidly assign that name forever so that the fixed construct might be analysed, categorised and mechanised into systematic logic where known inputs link to clearly defined outputs (Tsoukas, 1998). When this happens, we move from innovation, improvisation and experimentation to detailed planning and reverse-engineered, analytically optimised frameworks upheld by the institution.

Figure 1 has two large grey arrows illustrating two paradoxical, yet intertwined processes of convergence and divergence from the dominant paradigm. While some operators may employ a multi-paradigmatic approach to innovation most practitioners will adhere to a single dominant or parent paradigm. Regardless of whether it involves a solitary or multiple social paradigms, the process of innovation features a tacit cognitive activity where one reflectively considers the institutional or group paradigm and then iteratively engages in part of the innovative process by converging to some of the legacy frame and core paradigmatic structures. One military example of this is found in the decades leading up to the September 11, 2001, attacks where the U.S. Air Force sought to decommission the slow-moving, close air support A-10 fixed wing attack platform. Even after the shift toward counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations in regions where the enemy had no air force or robust anti-aircraft capabilities, the Air Force continued to propose newer, multi-mission craft that should replace the aging ground support aircraft that was enormously popular with ground forces (Zimmerman et al., 2019, p. 205). The Air Force feared losing air dominance, demonstrating paradigm convergence to their own service identity and deep philosophical position on complex warfare, and offered innovative options that adhered to these self-relevant positions.

The second grey arrow in Figure 1 is paradigm divergence and is the opposing, yet intertwined, process of challenging and disrupting the institutional paradigm. The aim is that innovative activities break through barriers that otherwise are forbidden spaces to think differently. Paradigm divergence requires the operator to reflect on that same legacy system and the dominant paradigm occupying the organisational mode for interpreting complex reality, so that one might improvise and ideate outside of these limits. An example of military forces innovating in paradigmatically divergent ways is found in how the U.S. Army and Navy struggled after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The end of the Cold War ushered in identity crises for both services, in that the sudden fall of the primary military rival meant that ‘the Army lost its conceptual anchor. Having achieved a sort of victory without war, the Army faced mounting budget cuts and uncertainty as to whether the driving concepts of the Cold War era would survive in a world where the United States stood alone as a superpower’ (Zimmerman et al., 2019, p. 196). The Navy too would experience this as their 1980s Maritime Strategy required a near-peer naval rival and, without the Soviet naval threat, ‘the concept of a global war at sea, such as that described in the Maritime Strategy, dissipated. So too did the apparent need for a high-end blue-water Navy’ (Zimmerman et al., 2019, p. 197). Both military services in the 1990s would spend the decade cycling through war paradigm divergence, while also iteratively looping back to efforts to converge with the earlier legacy frame, despite security challenges being quite different from the earlier Cold War context.

5. Moving from the concrete legacy to the emergent and abstract

The unintended shift from sensemaking and reflective practice to that of a concrete, action-oriented mode of reverse-engineered planning is done to enhance coordination and uniformity by the organisation desiring convergence. Weick argues:

people who are preoccupied with coordination tend to be guided by the name of the original experience rather than the qualities that were observed and felt at the time of imagining, forming and shaping. If significant details occur that lie outside the reach of these names, then coordinated people will be the last to see them and the first to be affected by them unless poets [reflective practitioners, innovators, improvisationalists] intervene (Weick, 2011).

Thus, while the institutional preference orders innovative activities moving from the abstract to the concrete, the opposite is actually in play. ‘Concrete’ thinking that occurs immediately in the fantastic and flux will stymie any subsequent reflective thinking, detour experimentation and improvisation so that deliberate action is orchestrated entirely in fixed names and categories that are part of the legacy frame of institutionalised, convergent thinking. Examples of the legacy frame include military doctrine and ordained managerial decision-making methodologies (the Joint Planning Process, the Military Decision-Making Methodology, or the Marine Corps’ Decision-Making Process).

Innovation unfolds not in a manner that supports the existing institutional belief systems and legacy war paradigm, but so that it is disrupted, deconstructed and reconfigured in previously unimagined or unrealised forms and functions. Thus, the movement from the fantastic and flux becomes an iterative journey to explore and then shatter the previously concrete. Terminology already fixed to ideas and patterns are re-examined, linkages broken and new formations prototyped in a fluid, temporary and even playful manner of exploring. Thus, the operator innovates by moving from the concrete into abstraction while flowing through Figure 1 in iterations of hunch and flux, taking anything concrete and fixed in the legacy system framing by the institution (doctrine, theory, models, methods, along with the ontological and epistemological underpinnings therein) so that as experimentation and prototyping progresses, one moves into greater abstraction as the innovator moves toward decision and deliberate action.

Figure 2 illustrates one way to show the iterative process of cycling from the legacy system and assumed concreteness to abstractions that move hunches from the flux and back into the fantastic to improvise, experiment and create. Figure 2 simplifies what is difficult to depict in a linear mapping, as the cognitive unfolding of innovative activities itself cannot ever be mapped in any ideal form. It differs for every operator and in every context. Figure 2 does highlight the nuanced distinction between disrupting, deconstructing and reflecting upon one’s institutional paradigm and the legacy frame through a convergent and divergent iterative process. Innovators moving from flux to hunch are ideally master practitioners with deep, tacit understanding of their craft.

Just as improvisation draws from one’s historical knowledge, wisdom and deep experience that is mapped within the institutional legacy frame, it must move iteratively through convergent and divergent paths. These are intertwined, but broadly an experimentation or improvisation that blends institutionally known and valued constructs with novelty has a convergent aspect to the hunch or prototyping. A refined ideation that challenges or disrupts the legacy frame in a divergent path will provide novel abstraction beyond those institutionally managed limits. Figure 2 is insufficient and likely an oversimplification in that there likely is no clear distinction between convergent and divergent iterations of moving from flux to hunch, but it is depicted as such for readers that are unfamiliar with these concepts. Tacitly, most thinking flows in an unmappable, emergent, dynamic process that changes each time an operator attempts to improvise or create.

Therefore, deliberate action should not be interpreted exclusively in a single paradigmatic mode where the legacy frame imposes some paradigmatic convergence. Instead, operators move in iterations of flux and hunch, improvising and cycling back convergently and divergently so that deliberate action is reconceptualised. Action may be considered systematically, in the western classical configuration of ‘ends-ways-means’ and a reverse-engineered causal mapping from a preconceived future state to that of the present, or in alternative ways of understanding activity that require alternative war paradigms to access. This disruption of legacy rigidness opens the innovative process up so that different ways of conceptualising complex reality are appreciated in this unfolding creative process. It also changes what we mean by ‘deliberate action’ in that those words no longer correspond exclusively with one institutional dictionary. Artistry and creative flow opens up new pathways to realise emergent frames as illustrated in Figure 2 where such abstraction is otherwise unavailable for those imposing the illusion of moving from the abstract to the concrete. Indeed, the creative flow moves in opposition, from the previously concrete, if illusionary, to the novel expanse of abstraction and potentiality.

Returning to Figure 1 so that the entire innovation process is completed, operators then move from refined ideation into a decision that is paired with deliberate action. Action is frequently only interpreted using a Western, technological and scientific framework that rests upon ancient Greek natural philosophy. This philosophy causes preconceived goals in the ideal to be forced into a future real world via the deliberate, heroic action of the operator. Deliberate action also should take a multi-paradigmatic perspective where we can train, educate and reform our military doctrine to recognise the limits of our preferred war paradigm, and then consider beyond those limits and how an adversarial, alien war paradigm is not the same nor will conflict with such an adversary bend the knee to our singular manner of interpreting reality.

In Eastern thinking, the notion of ‘action through non-action’ is where systemic logic considers the potentiality of unfolding systems, the interdependency of paradoxical yet intersectional, complex relationships, and how one might perform actions ‘up-stream’ when there is little or no system resistance so that, later on, there is no action necessary as the down-stream flow will cause future systemic change to flow along the new path designed by the non-acting strategist (Jullien, 2004, pp. 15–28, 148–149, 178–183). Whether considering from a Western, Eastern or more desirable ‘multi-paradigmatic’ perspective, the reflective practitioner moves to enact a purposeful implementation of creative thought into deliberate action. Although this notion of travelling from one institutional frame or paradigm to another is almost entirely non-existent in military theory and doctrine, these concepts do exist in other disciplines and fields. Schultz and Hatch (1996) offered that ‘paradigm crossing’ could lead to ‘interplay’, where instead of bridging across specific and linear zones between adjacent social paradigms, researchers could use simultaneous recognition of both contrasts and connections between paradigms. Schultz and Hatch (1996) explain:

… what is essential to an interplay strategy is the maintenance of tension between contrasts and connections.

… In interplay, the researcher moves back and forth between paradigms so that multiple views are held in tension. Thus, interplay allows for cross-fertilization without demanding integration, which suggests a criterion for selecting between crossing strategies: If one wants to take advantage of cross-fertilization between the ever-growing number of paradigms, while maintaining diversity, then interplay is the preferred strategy for paradigm crossing (Schultz & Hatch, 1996).

This is easier said than done. The curiosity and intellectual strength needed to depart one’s well-established, institutionally enforced worldview requires the operator to dodge, dip and dive through many obstacles. Paradigms operate smoothly when we comply with how they explain the world, and if we dare question the frame that we are given, certain paradigmatic defences kick in. When chaos, confusion and uncertainty pop up in how we are experiencing reality, the paradigm is designed to keep operators focused inward, not outward. If anything, the user must figure out how they might use the rules and processes created by the paradigm (our decision-making methods, encoded in our doctrines) more effectively so that we are further wedded to the frame. Instead of finding a way out to another potentially better vantage point beyond the paradigm, we are forced to stick within the institutional box. Karl Weick (1988) explains:

Explanations that are developed retrospectively to justify committed actions are often stronger than beliefs developed under other, less involving, conditions. A tenacious justification can produce selective attention, confident action, and self-confirmation. Tenacious justifications preconfigure both perception and action, which means they are often self-confirming (Weick, 1988).

System propensity in a complex, dynamic world means that the only constant in life is change, and the above commentary on the need for progress is part of an ongoing struggle between the complex reality unfolding around human beings, and the socially constructed second order of reality maintained collectively in their minds (Schultz & Hatch, 1996; Tsoukas & Hatch, 2001). Complex systems are perpetually in an emergent, illusive and dynamic state of change toward some unpredictable state of propensity. Our frames aid us in explaining reality, but also work as sociological prisons that prevent us from interpreting the complex world in any other way. Humans may utilise one paradigm or another to make sense of this fluid, ever-changing reality, and arguably in certain contexts of war, the victors ended up using a more effective social paradigm than the opponent. Equally feasible is the opposite, where one group might simply have superior resources, technology and time yet is miraculously able to drag itself to the victory circle using the inferior war paradigm and blunt force. Either way, operators that conceptualise opportunities and decide to enact activities will then experience the real-world consequences of these efforts.

6. Innovation: decisions, actions and consequences

When operators decide to act, these actions have consequences. All consequences impose some order of emergence, with some activities merely becoming inconsequential ripples on the water that cancel out quickly and without much notice while other consequences influence significant systemic transformation. As complex systems are sensitive to initial conditions, the metaphor that a hurricane might be formed by a single butterfly’s wings is a useful way to consider Figure 3 (Tsoukas, 1998). All activities impact the future propensity of a complex system, and by doing any action, the operators that rely upon the social construction of a shared paradigm cannot avoid their activities, not shifting that legacy frame into some new configuration (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Burrell & Morgan, 1979; Doran, 1989). Changes might be unperceivable, or they may take on seemingly chaotic or catastrophic orders of magnitude.

Systematic logic, if applied to the emergent transformation of complex systems, might encourage operators to seek to ‘find the butterfly that caused the hurricane’. This is when one confounds how complex systems are not just non-linear, but also are not analytically reducible into clear ‘cause and effect’ relationships. There is no single butterfly that causes a hurricane to form months later due to the flapping of wings creating fluctuations in weather that culminate in a massive storm. Instead, there are thousands of butterflies that are part of the overarching system that contributed to the emergence of a hurricane, and while one of them might have been the original wing flapper, it is not possible to mathematically isolate or reverse-engineer a causal pathway to that single insect. Instead, the aggregate of many events creating unique, non-repeatable and non-reversible activities results in an emergence of a new system configuration that can only happen once and cannot be rewound like an audio tape or movie. Systematic logic and the extension of natural science theories[6] into a scientific framing of war would become championed by theorists such as Jomini, Clausewitz, Scharnhorst and Fuller throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Heuser, 2010, pp. 102–110). Systems theorist Jamshid Gharajedaghi (2011) explains this pattern of military ontological formulation where states at war were reduced to individuals engaged in duels, and human components such as bones, cells and organs were associated with state-level entities and complex warfare:

The biological thinking or living systems paradigm, which lead to the concept of the organization as a uni-minded system, emerged mainly in Germany and Britain, but then caught fire in the United States. The underlying assumptions and principles of the biological mode of organizations are also simple and elegant: an organization is considered a uni-minded living system, just like a human being, with a purpose of its own. This purpose, in view of the inherent vulnerability and unstable structure of open systems, is survival.

… Although uni-minded systems have a choice, their parts do not. They operate based on cybernetics principles as a homeostatic system

… The operation of a uni-minded system is totally under the control of a single brain, the executive function, which, by means of a communication network, receives information from a variety of sensing parts and issues directions that activate relevant parts of the system (Gharajedaghi, 2011, p. 11).[7]

Were we to do this in a massive simulation that could even approach the sensitivity of a complex, dynamic system, each time we reversed back to the start, an entirely unique and dissimilar unfolding would occur. The linear-causal act of the single butterfly is an ideal but does not ever exist in the real. It only exists mathematically as a core part of the theoretical necessity of emergent, complex systems but is simultaneously an impossible-to-isolate component that is a synthesis of the entire propensity of a complex system in transformation. Pursuing reductionism or the epistemological position that ‘the world can be completely understood and that such understanding can be obtained by analysis’ represents a fundamental misunderstanding of complexity by modern militaries (Gharajedaghi & Ackoff, 1994, p. 29). Modern military quests to locate individual butterflies within complex, dynamic conflict settings underpin what is a Newtonian stylisation best echoed on battlefield patterns of the seventeenth through early twentieth centuries, where prominent war theorists such as J.F.C. Fuller would influence nearly all modern Western military management of decision-making through a reductionist, analytical, deductive manner of rationalisation:

If we understand the true reason for any single event, then we shall be able to work out the chain of cause and effect and, if we can do this, we shall foresee events and so be in a position to prepare ourselves to meet them.

… military power is controlled by similar laws to those which govern [physical laws of nature] force, consequently the one aim of the soldier is to harmonize his mind to the workings of these laws (Fuller, 1925/2012, pp. 94–95).

Complexity rejects such attempts, despite modern military fixation on reinterpreting complex systems through linear-causal, mechanistic ways and means. In particular, innovation and change occur not by cautiously extending established ideas of the legacy system incrementally and convergently, but through disruption and destruction of the old in search of the new (Bureau, 2013; Coral et al., 2016; Stanczak et al., 2021). Figure 3 presents some of this in an unavoidably clunky oversimplification. Innovators move from deciding to implementing their improvisation, experimentation or other activity so that there are consequences that begin unfolding in complex reality. The system changes in unpredictable, potentially unimagined ways. As those manifestations unfold and the complex system exercises dynamic transformation, the institution’s legacy frame itself undergoes a drifting effect due to the living users of the social paradigm themselves being pulled in this current toward a yet-to-be unrealised future state. As operators reflect as they practice, they are sensemaking and adapting to how the system transforms in this intertwined journey of innovation (Weick, 1996, 2006b, 2011). Often, the institution’s legacy frame imposes particular value sets that draw from deeply held belief systems where an experiment might be considered as a good or bad consequence, assuming that the emergent outcome either validates earlier hypotheses, or perhaps generates surprise or uncertainty. Non-reflective practitioners might move exclusively in a convergent iteration as shown in the top arching portion of Figure 3, where subsequent iterations of improvisation and innovation conform to legacy frame conditions where values are used to interpret how consequences might be evaluated (Chia, 2013; Ferry & Ross-Gordon, 1998; Schön, 1984; Visser, 2010). This too can be problematic, as Mrazek cites Admiral Mahan’s warning that officers are ‘already disciplined … prepared to accept rules … without hesitation, and frequently with too little reflection’ (Mrazek, 1968, p. 17).

Often, innovation is a messy, irregular, and nonlinear process that unfolds not through multiple linked objectives that are realised and validated, but through many instances of failure and confusion. Failing is an integral part of innovation, yet paradoxically it is a mainstream target for institutional avoidance in modern militaries. ‘Failure is not an option’ often permeates the social paradigm of a military organisation so that innovation and creativity are marginalised or potentially eliminated so that system stability and an institutionally sanctioned sort of orderliness is maintained. It is impossible to determine if creativity is best accomplished for military applications in groups or by individual effort, yet Mrazek makes some compelling arguments that creative ideas ‘do not spring from groups. They spring from individuals’ (Mrazek, 1968, p. 18). Mrazek, also citing philosopher William Ernest Hocking, posits: ‘Could Hamlet have been written by a committee, or the Mona Lisa painted by a group of conferees? The answer is emphatically “No!” Creative ideas do not spring from groups. They spring from individuals’ (Mrazek, 1968, pp. 143–144).

However, in all examples of innovation, those that set out on their journey to create did not set their destination to be where they ultimately arrive, and most always that journey is beset by necessary conditions of failure, often profound and repetitive. The famous tale of Thomas Edison failing 9,999 times so that he finally could innovate and successfully produce the first working lightbulb on attempt number 10,000 is important to consider here. Without reflective practice, and innovators moving wittingly or unwittingly through how Figure 3 frames the emergent process of creativity, discovery, failure and reflection, one simply cannot succeed in producing what the organisation needs tomorrow but does not yet exist today.

7. Conclusion

Innovation is risky, messy and rarely unfolds in some orderly or logical flow of activities and events. Humans are further challenged by how we experience reality in a linear progression of time and space, where complexity and emergence seem almost obvious in hindsight but impossible to anticipate with any accuracy on the horizon. Our expectations of the future are typically conceptualised in an ends-ways-means, reverse-engineered arrangement of ancient Greek logic. This Western mindset permeates our interpretation of reality and demonstrates a perpetual military tension between what is science in war and that which can only be associated with creative artistry.

War represents the most violent, chaotic and destructive of any human behaviours capable of this species, and all human existence features a dizzying array of war activities that appear enduring and potentially part of the human condition. Innovation represents a foundational aspect of why our species differs from all other known life. We cannot only imagine the real, but we can fantasise about entirely unreal and never-before-considered combinations of novel things and concepts. Some can only exist in the artificial fantasy of our minds, while others can be teased out into reality so that our invention generates systemic transformation. Innovation above all else is the defining characteristic of why humans cannot ever be limited by natural laws or social rules. Prior to 1903, it was impossible to fly in a controlled-power flight that was heavier than air. Prior to 1969, no human had set foot upon another celestial body. Prior to 1997, humans were bounded by biological rules so that reproduction or duplication of one animal could not be artificially cloned. Before 2003 and the mapping of the human genome, the foundational bits that make our species what it is were unavailable to us. Innovation smashes barriers and opens entirely new doors for humans to walk through. This of course exists in war, and the deterrence of such organised violence.

Modern military organisations are comfortable with military science, in that a technological rationalism consumes how we process reality and attempt to institute order into a chaotic world. In many regards, modern societies demonstrate mastery of military domains such as air, land and sea. We have invented an entirely new digital domain called cyberspace within which people can exist and also wage war in an entirely artificial plane of existence. Since humans first left this planet, they now are expanding across space as a new domain to exist in. Throughout our existence and within every armed conflict, innovation is a powerful and defining thread for which progress occurs and meaning is generated so that all social paradigms can somehow make sense of our complex reality. Our reality is about to get much more complex, and far larger than our species is comfortable with. In technological developments concerning artificial intelligence, we likely will become highly dependent upon increasingly exquisite AI, even up to levels where our humanity is unable to appreciate what the artificial can understand and experience. Our species is close to becoming a multi-planetary species, able to colonise and commercially exploit cislunar space and the inner solar system. With this expansion, war will accompany our species, likely transforming into even more unusual and surprising configurations and contexts that have little or no historical precedent (Zweibelson, 2023b, 2023c).

Modern militaries are paradoxically able to channel innovation in certain aspects of complex warfare quite comfortably, such as in technological or immediate and tactical applications. Yet we struggle with anything beyond these narrow areas of warfare, particularly with systemic appreciation of broader strategy and complex emergence of unanticipated consequences in war. We seek to standardise everything in war into some orderly or seemingly stable framework, including innovation. We even attempt in our doctrine and managerial methods for decision-making position military artistry in physical, mathematical or engineering formulations. This illuminates what is often an institutionalised resistance to change, disruption, uncertainty and the destruction of cherished or ritualised beliefs and behaviours. Innovation is not developed or capitalised in this pragmatic, artificially sterilised mode of human thought and action. Instead, it occurs in the fantastic, often manifesting in profoundly unusual or counterintuitive ways. The more disruptive an innovative concept is, the higher likelihood the institution will resist it greatly and potentially be blinded in even recognising it. Mrazek writes eloquently on this, and his passage is presented below in full as an appropriate concluding perspective that military leaders at the top of our services and institutions might consider carefully:

A creative person is also motivated by a desire to do the rigorous work required to test and modify his ideas and insights. Herein lies one of the most difficult tasks of the creative personality because it means that he has to pursue his ideas despite the great demands which will be made upon him intellectually and physically in carrying the ideas through to conclusion. Frequently, he will encounter listless to unreceptive supervisors or compatriots as he tries to sell his ideas. His enthusiasm will be jarred, his energies will be sapped, and unless he is an unusual individual who is able to shrug off or overcome these and many other obstacles set to deter him in his fulfillment, he will never realize his idea no matter how unique, valuable, or basically good it is. This is the experience of many artists; this is the curse of man toward man (Mrazek, 1968, p. 156).

This paper including the three other papers in the four-part series (Zweibelson, 2024c, 2024b, 2024a) sought to explain these tensions and presented a different way that modern militaries might conceptualise how innovation unfolds, and how the organisation might transform its culture, belief systems, mental models and decision-making methodologies to incorporate theories on innovation that do not exist in the dominant war paradigm employed across the enterprise. Such change would require a generational rather than immediate gaze so that the entire institution might reconfigure in an enduring and powerful shift. This transformation would make military artistry not remain some abstract association with magical ‘genius’ and random realisation, nor would it ever transition into an orderly recipe or formula the military might imprint upon all future operators. Instead, militaries must consider how military artistry could be enhanced so that innovation oozes not through the seams of an institutional strait jacket but flows openly and in parallel with the well-developed scientific mastery of how modern defence organisations prepare and execute dangerous security activities.

Some social paradigm theorists insist one cannot leave one’s dominant paradigm, while others support a multi-paradigmatic mode of inquiry. All social paradigm theorists do agree that no human thought can occur without grounding in a social paradigm. There is no possible ‘supra-paradigm’ perspective above all other social paradigms.

Ackoff does not specifically use ‘abductive logic’, but his explanation of designing with novelty toward problem dissolution is entirely within how abductive logic is differentiated from inductive and deductive logics in application.

This is not to suggest that improvisation is accomplished on some random whim, spontaneous and intuitive but available to any practitioner. Improvisation done by an amateur will be as clumsy and error ridden as their regular attempts to follow set patterns and processes. Masterful practitioners draw upon deep, tacit knowledge, experience and wisdom so that their acts of improvisation produce not just ‘something out of nothing’ but something profound and novel that might transform the system dramatically.

These references address social paradigm and multi-paradigm dynamics by which war and conflict must be encompassed. However, these authors do not specifically consider ‘war paradigms’ or mention war directly.

Warfare is complex and prevents linear-causal testing where one isolates a subcomponent, tests the idea, and then reverses the system repeatedly to evaluate performance variation across different prototypes. Instead, ideation and experimentation may occur in computer simulations, staff ‘war games’, and also in training contexts such as how national training centres feature a ‘free playing opposing force’ that can think, act and respond as a military force attempts to execute their missions in a real-world simulation. In situations where combat losses and fatalities are simulated, leaders may have greater cognitive tolerance to try out otherwise unpalatable, unorthodox or controversial ideas.

The natural sciences in this case include physics, geology, biology and chemistry.

Gharajedaghi (2011) does not specifically address Westphalian nation states or modern war theory in this citation, but more broadly addresses all of western society in its modernisation, industrialisation, and technological transformation via modern scientific thinking.