1. Introduction

Malaysia is a maritime nation in Southeast Asia, bound by the Strait of Malacca and Indian Ocean to the west and the South China Sea and Pacific Ocean to the east. Malaysia’s maritime environment is shared with neighbouring states belonging to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Malaysia is one of five founding members of ASEAN. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Article 56, states the coastal states’ rights, jurisdiction and duties in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Malaysia’s EEZ covers an area of 334,671 km2, while that of the entire ASEAN is about 9.4 million km2.

Malaysia and most of the ASEAN member states maintain extensive maritime areas that are essential resources for food, minerals and economic trade. The maritime economy, also known as the blue economy, contributes about 40% of Malaysia’s gross domestic product (GDP). About 90% of Malaysia’s trade is seaborne and an estimated 80,000 ships pass through the Strait of Malacca yearly (Bernama, 2023). Malaysia is the world’s third biggest trader by sea (Cogoport, 2022), with the fisheries industry’s production value of MYR14.88 billion (AUD$5.10 billion) in 2021 (Department of Fisheries, 2023). Thus, securing the maritime environment is vital to ensure access to fishing resources.

In 2020, the Malaysian Ministry of Defence released the 2020 Defence White Paper which highlighted the aim of defending the Malaysian Maritime Zone (MMZ)[1], strategic waterways and critical lines of communication as a matter of national defence interest (Ministry of Defence, 2020). To achieve this aim, one of Malaysia’s national defence objectives is to develop multiple domain capabilities to detect, deter and deny threats within the core, extended and forward areas as shown in Figure 1 (Ministry of Defence, 2020). Figure 1 shows the concentric layers whereby the core area covers Malaysia’s land, while the extended and forward areas cover the EEZ and extend beyond the EEZ, including the sections of the South China Sea. Multiple domain capabilities, including cyber electromagnetic, air, maritime and land domains, are needed to secure Malaysia.

Security threats to Malaysia’s maritime environment can be divided into two categories: traditional and non-traditional threats. Traditional threats are challenges to sovereignty and international relations. From a security perspective, these are referred to as military threats and originate from other states (Daihani, 2019). The main traditional threat within the MMZ is China’s nine-dash-line claim to most of the South China Sea and their development of military bases on many islands. On the other hand, non-traditional threats include terrorism, piracy, human, drug and arms trafficking, and environmental degradation due to illegal fishing, waste dumping and ship dismantling (Dabova, 2013). In general, non-traditional threats are those that affect human security, including economic, political, food, environmental, personal, community and health security.

To develop a strategy to secure Malaysia’s maritime environment, it is crucial to optimise and prioritise the allocation of resources. Prioritisation can be guided by identifying the economic losses from maritime threats. In 2019, maritime threats for the ASEAN region incurred a total loss of about USD$10.8 billion. This cumulative comes from the three categories: (1) ~USD$3.5 billion (32%) from maritime incidents, terrorism, theft, robbery and piracy based on cargo and hull insurance claims (International Union of Marine Insurance, 2021); (2) ~USD$1.3 billion (12%) from environmental security (Long, 2020); and (3) ~USD$6.0 billion (56%) from illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUUF) (Malik, 2023). While the economic losses from non-traditional threats can be roughly obtained, it is difficult to quantitatively assess the losses from traditional threats. Nonetheless, pursuing a strategy to combat threats that pose a significant economic impact could justify government spending. Moreover, as these maritime threats are interrelated, pursuing a strategy to solve one issue could provide mutual support for combating other maritime threats.

Despite efforts by Malaysia and other ASEAN members to address IUUF, the economic losses remained significant over the past decade. To prioritise Malaysia’s efforts to secure its maritime environment, it is worth noting that the 2019 economic loss due to IUUF is ~56% of total losses to non-traditional security threats within ASEAN. Malaysia’s economic losses for the same period are ~USD$1.4 billion (Vethiah & Zul Kepli, 2021). To appreciate its significance, this loss is ~23% of ASEAN’s loss, ~0.38% of Malaysia’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 42.8% of Malaysia’s defence budget (USD$3.27 billion). Hence, prioritising IUUF over other threats could have a profound impact on Malaysia’s economy as well as provide indirect benefit to both environmental and human security.

Malaysian joint operations to combat IUUF have been partially effective. However, Malaysia lacks the capability to consistently detect, identify and track illegal fishing vessels. With limited resources and Malaysia’s vast EEZ, addressing IUUF remains a significant challenge that requires identifying the modus operandi of illegal fishers as well as devising cost-effective solutions for surveillance and enforcement. I propose integrating space-derived services into Malaysia’s security framework to provide enhanced surveillance capability to monitor its maritime equities. I will provide an overview of capabilities and associated cost-benefit when using commercial and sovereign space services. Lastly, I will discuss potential areas of collaboration within ASEAN and other neighbouring countries that are willing to support a collaborative security strategy and a regionally focused space capability to solve an important economic and environmental problem.

2. Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUUF)

IUUF is commonly referred to as any fishing that violates fisheries laws or happens outside existing laws and regulations on the high seas or in areas under the national sovereignty of a state (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], 2001). These fisheries laws regulate ocean governance by protecting and conserving the environment, habitats, ecosystems, biodiversity, fishers at sea and human rights (Partelow et al., 2023). IUUF has become a significant problem in the fishing industry, with some operators seeking to circumvent international laws and practices to maximise profit. According to the FAO, 34.2% of the world’s fish are over-exploited, threatening the long-term viability of coastal economies and the global seafood supply (FAO, 2020). These activities are conducted by state and commercial fishing enterprises (Brush, 2019).

Illegal fishing refers to fishing activities of a national or foreign vessel in the waters of a state or on the high seas violating the laws and regulations of a state, flag state or regional fishery management organisation. Illegal fishing includes using banned fishing gear, fishing without a licence or fishing for prohibited species. IUUF vessels often use illegal trawler nets, which will catch everything, including small fish, and destroy the corals during the catch (Shah & Goh, 2021). Unreported fishing refers to unreported or purposefully misreported fishing activities. While underreporting catch can be intentional and unintentional, fishing vessels can purposefully underreport to circumvent quotas or avoid taxation and duties for their catch. Unregulated fishing refers to fishing activities in the Regional Fisheries Management Organisation (RFMO)-controlled waters inconsistent with or against the conservation and management in the area or for fish populations with state responsibilities under international law. Unregulated fishing activities include vessels with no nationality or those flying the flag of a state not a party to that organisation when operating in RFMO-controlled waters (FAO, 2001).

The impact of IUUF on Malaysia is not limited to economic loss but also impacts the marine environment and fishing communities. Overfishing, one of the major effects of the IUUF, is a significant issue, with up to 30% of global catches being illegal or unreported (National Intelligence Council, 2016). Overfishing threatens sustainable fisheries and conservation measures. The IUUF targets already depleting stock, often in areas closed to fishing (Agnew et al., 2009). In 2022, fish sightings in Malaysia had reportedly decreased by up to 70%, especially in the north of the peninsula (Loh & Malik, 2022). IUUF also resulted in many Malaysian fishermen leaving the industry, especially from Kemaman in Terengganu, and Kuala Sedili and Mersing in Johor (Shah & Goh, 2021). IUUF losses in countries such as Indonesia and Thailand have flow-on effects for Malaysia by reducing Kuala Kumpur’s food security. Malaysia has the second highest consumption of fish and seafood per capita (46.9 kg per capita) behind Cambodia’s 63.2 kg per capita (Loh & Malik, 2022).

2.1. Modus operandi

For Malaysia to adequately address the IUUF problem, it is essential to understand the modus operandi of the perpetrators. This will enable the generation of appropriate solutions with minimum resources and optimum outcomes. The modus operandi described by the methods used for IUUF are: (1) Automatic Identification System (AIS)[2] dark activity; (2) flag manipulation; (3) vessel identity alteration; and (4) transshipment at sea (Brush, 2019).

Turning off the AIS (or AIS dark activity) is the most frequent modus operandi of IUUF perpetrators. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Regulation V/19.2.4 mandates the use of AIS for all vessels above 500 gross tonnes (GT), any vessel above 300 GT on an international voyage, and all passenger vessels. The Centre for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS) reports that about 80% of vessels involved in IUUF are turning off AIS before entering the EEZ (Brush, 2019). With AIS turned off, fishing vessels can enter a country’s EEZ without a permit and fish illegally because they are undetectable for extended periods.

While loss of AIS signal is not always a crime and can be caused by factors such as the absence of AIS receivers, bad weather or broken equipment, it can be an indicator of deliberate concealment of actions. Figure 2a shows the classic example of AIS dark activity whereby the vessel has turned off the AIS transponder for periods before being escorted by the authorities to port (Welch et al., 2022). Thus, it is crucial to have a system to detect these vessels when AIS is turned off.

Analysing hotspots for AIS dark activity can identify potential areas where IUUF can take place. This analysis enables the maritime enforcement agencies to concentrate on the hotspots for optimum effect. AIS dark activity hotspots generally can be found in the EEZ and Maritime Protected Areas (MPA) (Welch et al., 2022). The duration of AIS dark activity may refer to the time it takes the perpetrators to enter and exit the EEZ, which will determine the response time by considering distance and coverage area. Figure 2b shows one of the AIS dark activity hotspot in Indonesia. The hotspot is ~20,700 km2 and located within ~100 nm from shore. However, identifying these AIS dark activity hotspots requires the RFMOs to build their regional database before executing this concept.

Apart from vessels turning off their AIS, Brush (2019) also reported that IUUF vessels use flag manipulation and vessel identity alterations to avoid detection and attempt to confuse authorities. Flag manipulation in IUUF includes changing the flag state, using multiple flags simultaneously and no flag at all. Moreover, altering vessel identity refers to the vessel repeatedly changing identifiers such as vessel name, call sign, Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI), and altering the exterior (that is, paint colour). Multiple ships can share a single licence or vessel authorisation to save money by pretending to be an authorised vessel (Brush, 2019).

IUUF perpetrators also employ transshipment at sea, which refers to the transfer of supplies, crew and cargo between two fishing vessels or between a reefer and a fishing vessel. While transshipment at sea is a permitted practice governed by RFMO observer programs, there is a high probability that fish obtained illegally are inserted into the legal supply chain without the RFMO’s monitoring. Additionally, unregulated transshipments facilitate other maritime crimes like drug, weapon and people trafficking. For instance, transshipment makes it easier for crew members to move between ships at sea without being inspected in port (Brush, 2019).

To further understand IUUF modus operandi, it is crucial to identify the common characteristics of vessels involved in IUUF. Figure 2c plots the length of vessels involved in IUUF within the ASEAN region between 2015 and 2021 (RPOA-IUU Secretariat, 2021). These vessels are all weighted 300 GT and above, meaning they should be equipped with AIS. The length of these vessels varies from 40 metres to 102 metres. The average length of reefer vessels or supply vessels (red) is 76±19 metres while that of fishing vessels (blue) is 52±7 metres.

To summarise this section, IUUF activities have impacted Malaysia’s economy and also negatively impacted the marine environment, fishing communities and other transnational crimes. The most frequent modus operandi of IUUF activities is AIS dark activity. Continuous monitoring of the EEZ will require substantial resources and is nearly unachievable; thus, using the AIS dark activity hotspots will allow the few available resources to be concentrated on high-risk specific areas in certain periods.

3. Malaysia’s governance framework to address IUUF

Malaysia’s regulatory regime in addressing IUUF is described in the legal framework of domestic, regional and international efforts. The domestic framework is shaped by the Fisheries Act 1985 which has been amended several times to increase the effectiveness in governing matters relating to fisheries, including the management and development of maritime and estuarine fishing (Ghazali et al., 2019). In addition, there are action plans such as a Fisheries Management Plan (FMP) and a National Plan of Action (NPOA). The regional efforts are mainly under ASEAN and the Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC). The international efforts are under United Nations (UN) and FAO frameworks. There are many regulations for mitigating IUUF, however, effectiveness relies heavily on surveillance and enforcement.

The effectiveness of surveillance and enforcement in the maritime environment reflects the capabilities and efficiency of the operations conducted by defence forces and civilian agencies. This is achieved through the three main maritime roles of defence, safety and security. The IUUF aspect is under the security role. Enforcement operation requires a whole-of-government approach to the detection, identification, tracking and apprehending of IUUF offenders. These capabilities mainly come from the Malaysian Armed Forces (MAF), Royal Malaysia Police (RMP) and Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA).

The primary enforcement agency for maritime security is MMEA which is tasked to prevent offences in the MMZ under the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Act 2004. The capability of MMEA includes an AIS monitoring application, eleven radars in the Malacca Strait, four radars in East Malaysia, a mobile surveillance unit, aircraft and patrol vessels. The RMP Police Marine assists MMEA in enforcement operation with aircraft and vessels. In contrast, maritime security falls under the MAF’s secondary role of conducting Military Operations Other Than War (MOOTW), including assisting civil authorities in enforcement (Ministry of Defence, 2020). In general, the capability of the MAF includes special forces, radars, aircraft from the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) and ships from the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN).

Malaysia has thee active joint maritime operations. One of the joint operations is internal within Malaysia, while two others are multilaterals with other ASEAN member states. In 2013, Malaysia established the Eastern Sabah Security Command (ESSCOM). Its role is to strengthen security in the eastern part of Sabah following the invasion crisis and prevent terrorist activities in the waters of Sabah (Alavi & Wan Husin, 2023). The two other multilateral joint operations include the Malacca Strait Patrol (MSP) and Trilateral Cooperative Arrangement (TCA). The MSP consists of Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and Thailand and was established in July 2004 to ensure the security of the Strait of Malacca and Singapore (Emmers, 2010). The TCA consists of Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines and was established in June 2017 to ensure the security of the Sulu Sea and the Celebes Sea (Rustam et al., 2022). Figure 3 shows the positive impact of the TCA joint operations on maritime terrorism within the operation area. The existing concept and joint operation show good coordination and participation in a whole-of-government approach and the ASEAN way of cooperation. However, despite strict enforcement measures by Malaysia and other ASEAN members, IUUF remains rampant over the past decades (Nehru, 2023). Figure 3 shows IUUF incidents across ASEAN (dark blue) and Malaysia (light blue) waters, with 29% of all cases affecting Malaysia (Information Fusion Centre (IFC), 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022).

Malaysia has taken a whole-of-government approach to address IUUF. The governance framework includes national, regional and international regulatory and action plans for combating the IUUF problems. Despite the excellent concept of maritime operation and the output of joint operations proving successful in reducing maritime threats, the IUUF economic losses remain high annually.

3.1. Current maritime security concept

Figure 4 shows the current maritime security framework utilised by Malaysia. This framework has three phases: (1) Integrated information; (2) Decision; and (3) Action. The first phase, Integrated information, is where all the intelligence is gathered and analysed. There are various sources of information related to maritime security, including information from the military, security agencies, open source and multinationals. The information from the military includes human intelligence (HUMINT), signals intelligence (SIGINT), imagery intelligence (IMINT) and open-source intelligence (OSINT). All this information will be integrated into intelligence reports with advisory actions in countering the maritime threats.

In the Decision phase, the authorities decide the actions to pursue based on the intelligence and advice received, national objectives and policies. The National Security Council (NSC) is Malaysia’s responsible authority, and the NSC may delegate this responsibility to others as needed. The importance of this part is to produce a strategic outcome through operational input.

The Action phase can be divided into three options: (1) Monitoring; (2) Enforcement; and (3) International partners or allies. Monitoring and enforcement utilise military or civilian agencies’ assets in identifying, tracking and arresting the target vessel. The outcome of monitoring action will be the intel report and mission report for enforcement operations. The output for the international partners or allies will be joint operations or information sharing similar to TCA (Krishnan, 2022). The incomplete information is one of the main weaknesses of this concept, which will significantly affect the operation in searching, identifying and tracking the suspected vessel during maritime missions.

The impact of incomplete information will increase the chances of the IUUF vessel escaping out of the EEZ when the search operations are prolonged. In addition, more assets will be required for the search operation.

3.2. Surveillance rate of effort

How can Malaysia combat IUUF? The first part of the answer is effective surveillance and detection. The second part is enforcement operations, which can only be executed if perpetrators are first identified. Here, we assess two options to increase detection: (1) increase the rate of effort in airborne surveillance; and (2) use of space services.

3.2.1. Air assets

For airborne surveillance, the rate of effort is the number of flights conducted for surveillance operations. Expanding this effort will increase the area coverage, resulting in more IUUF vessels detected. However, the cost required for these operations will increase. Using a RMAF CN235 aircraft to monitor the entire EEZ of Malaysia would take 13 flights based on the aircraft’s total visual area coverage (25,000 km2) and maximum flight time of seven hours. The operating cost is estimated to be ~USD$2700/hour[3] (Sandhills Global, 2024) which translates to USD$245,700/day, USD$7.4 million/month and USD$88.5 million/year to cover the entire Malaysian EEZ.

This assumption does not include a few considerations. First, prolonged high-intensity operations may cause the aircraft maintenance schedule to be due earlier than the planned time, ultimately costing more. Second, a high number of aircraft and crews are required to maintain this high-intensity operation. Third, additional aircraft may be required during enforcement activities. Fourth, aircraft are limited by bad weather and transit times. Most importantly detection does not equal enforcement. Therefore, spending this amount of resources does not promise it can reduce the IUUF losses as it depends more on how effective are the enforcement operations. Overall, increased airborne surveillance may be part of the answer to increase detection rate but the high financial and aircraft cost make it an unviable long-term solution.

Another method to increase the surveillance rate of effort is using the drone or Uncrewed Aircraft System (UAS). On 25 May 2023, the Malaysian Ministry of Defence announced the USD$91.6 million contract with Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI) for three new Anka-S drones and a single ground control unit, including two years of support (Arthur, 2023). Malaysia’s Anka-S is a medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) UAS expected to be delivered in 2025 and will be equipped with maritime intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) payload, including synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and electro-optical/infra-red sensor (Felstead, 2023). The endurance and loitering speed for the Anka-S is 30 hours, and 204 km/h will give more coverage than the CN235. Nevertheless, open-source data for the operating, maintenance and training costs are unavailable for comparison. Still, the initial cost of USD$91.6 million for three drones exceeded the assumptions for four years’ operating cost for three flights daily using CN235. Overall, drone technology has become a valuable complement to manned aircraft; however, it is also impacted by existing limitations on air power such as bad weather conditions, transit time and finite endurance.

3.2.2. Space assets

The high operational cost of using air assets for surveillance makes it worthwhile to resort to space-derived services, a technology from a different domain that may offer better comprehensive coverage of vast areas in enhancing maritime security and may also be augmented by airborne surveillance. Figure 5 tabulates the comparison between operating aircraft, satellites and UAS for detection in terms of area coverage, cost and time required to acquire data. This assumption using COSMO-SkyMed, an SAR satellite, costs USD$1600 per snapshot with area coverage of 200 km x 200 km (Geocento, 2023). The usage of satellites for surveillance is subject to the frequency of passes over the area of interest and the latency period from collection to processing and then to the user. However, the operating cost for UAS is yet to be determined as it will be delivered in the latter part of 2025. The general pros and cons of satellites, aircraft and UAS are listed as findings in Figure 5. This comparison shows the possible option of space services that can improve detection effectiveness. Thus, detailed research will let us know what space-derived services can offer.

Malaysia’s options to mitigate IUUF by increasing the surveillance rate will continue burdening its scarce resources. Whilst Malaysia’s UAS three MALE drones are expected to be delivered towards the end of 2025, they may not be able to cover all areas. Hence, the option of using space-derived services to detect IUUF vessels in EEZ with more cost-effective and comprehensive coverage should be identified in detail. Modern military operations are incomplete without space-based capabilities, providing crucial data for defence, deterrence and strategic decision-making. Using the same space-derived services in IUUF can also contribute to the military mission in combating traditional threats, especially in the South China Sea. It can support decision-making by providing timely and accurate data to complement the other domains.

4. Space-derived services for maritime surveillance

Space-derived services exploit the space domain to enhance maritime surveillance in providing cost-effective wide-area surveillance that can be used to complement existing air and naval capabilities. For the purpose of this paper, the space domain encompasses the space environment and the space system that is used as the framework to exploit it. The space environment is the region where atmospheric effects are negligible, and it encompasses phenomena that exist, celestial objects and interaction between them, including the vacuum of space, radiation, microgravity and celestial events.

4.1. Space Information

Different sensors and orbits will provide different space information output. For maritime security, key information will be sourced through: (1) Satellite-based Automatic Information Systems (S-AIS); (2) radio frequency (RF) for geolocation; (3) Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) for thermal detection; (4) passive imagery for high resolution and multi-spectrum photograph; and (5) Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) for all weather, day-night imaging.

S-AIS refer to satellites capable of receiving signals from AIS transponders. S-AIS is used for long-range reception; however, the AIS is only widely used in inshore areas with tower-based applications (tAIS) and radar (De Souza et al., 2016). S-AIS technology can also identify fishing activity for three dominant fishing gear types: (1) trawl; (2) longline; and (3) purse seine (De Souza et al., 2016).

RF tracking satellites can detect and geolocate electronic transmission from a vessel without the AIS. Even though using S-AIS can provide long-range reception, the most common modus operandi of IUUF is AIS dark activity, making the vessel undetectable when illegally fishing inside the EEZ. How do we detect this AIS dark activity? Commercial companies offer services tracking these ‘dark vessels’ using RF tracking satellites to monitor a wide swath of the RF spectrum for all radio and radar emissions. Every vessel has its unique RF signature, which is harder to trick or turn off than the AIS transceiver on the bridge. The satellites can geolocate this source of a unique RF transmitted like radio communications by the ‘dark’ vessels. The suspect vessel may shut off its AIS, but this technology can still detect them on other frequencies, regardless of day or night, fair or poor weather (The Maritime Executive, 2022). Figure 6a shows the AIS dark activity detected by RF tracking satellites (Unseenlabs, 2022).

VIIRS is a passive sensor that detects and measures visible and infrared images and global observation of the land, atmosphere, cryosphere and oceans. The capabilities of the VIIRS instrument are capturing daily high-resolution imagery across multiple electromagnetic spectrum bands, including the visible and infrared images of detecting fires, smoke and particles in the atmosphere (Cao et al., 2014).

IUUF activities continue on the ocean after sunset, with bright lights installed on the vessel to draw the fish to the surface, especially for squid, and to illuminate the deck or surrounding water for night fishing operation. These lights used by the IUUF vessels can be seen from orbit by the highly sensitive VIIRS satellites. NASA’s VIIRS satellite, the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership, has been operating to take nightly photographs of the surface (Cao et al., 2014). When linked with S-AIS using a sophisticated matching system it is able to identify vessels with AIS dark activity. The matching system provides the vessel’s data that do not match AIS, revealing that most of the detected bright lights are fishing vessels (Kroodsma, 2022). Figure 6b shows accumulated data of intense fishing activity at night off Southeast and East Asia from 2017 to 2021 (Kroodsma, 2022).

The high-resolution optical satellite imagery uses a passive image sensor such as a camera. The S-AIS data linked with RF and/or VIIRS will give you the detection of AIS dark activities. These detections may provide identification with the name and type of vessel operating when matching against AIS data. However, if there is no matching data from the AIS, it won’t be easy to know what type of vessel is being looked for. Identifying the vessels after detection is essential for enforcement operations. For security agencies to operate accurately, the types and features of suspected vessels are critical. Thus, a high-resolution optical satellite is essential for accurate identification and tracking. A high-resolution optical satellite can give a clear image of the vessels, including their colour, size, type of fishing vessel, and current heading and activities. These images will be useful when security agencies search from the air or sea. One of the IUUF court cases successfully won by Indonesia was using the DigitalGlobe satellite during enforcement in 2015 (Zeiss, 2017).

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) refers to a satellite with an active sensor capable of capturing radar images. Active sensors like SAR can operate anytime and are hardly affected by weather conditions (Kraetzig & Enright, 2023). Passive sensors do not emit radiation but function to detect and collect electromagnetic emissions. Because of this, passive imagery is frequently reliant on the day-night cycle (Kraetzig & Enright, 2023). Unlike passive sensors, SAR is able to work in poor weather conditions such as dense cloud cover. Detection of AIS dark activity using RF and VIIRS satellites can provide space information on the location of the IUUF vessel only when the vessels transmit radio frequency or use a bright light during illegal fishing. Satellites with S-AIS and SAR capabilities can detect dark vessels and provide vessel information linked to AIS or vessel size only without AIS (Soldi et al., 2021).

4.2. Space readiness within the region

Space readiness identifies national capabilities and collaboration arrangements that can support future maritime security developments. The World Population Review (2025) has released a ranking of countries with space programs based on seven operational levels of readiness, with level 1 as the lowest and level 7 as the highest. Only six ASEAN countries are using space technologies and all at operational level 2, which means having ground-based space activities (space agency) and operating satellites. In general, the ASEAN countries’ space technologies focus more on communication satellites for commercial use. As of 2023, Indonesia and Singapore are the only countries operating SAR satellites, while other countries subscribe to commercial SAR satellites’ space information. The usage of the subscribed SAR satellites is focused more on commercial and agricultural purposes and not for maritime security. Thus, the collaboration of space technologies between ASEAN countries for maritime security may be less likely to happen soon.

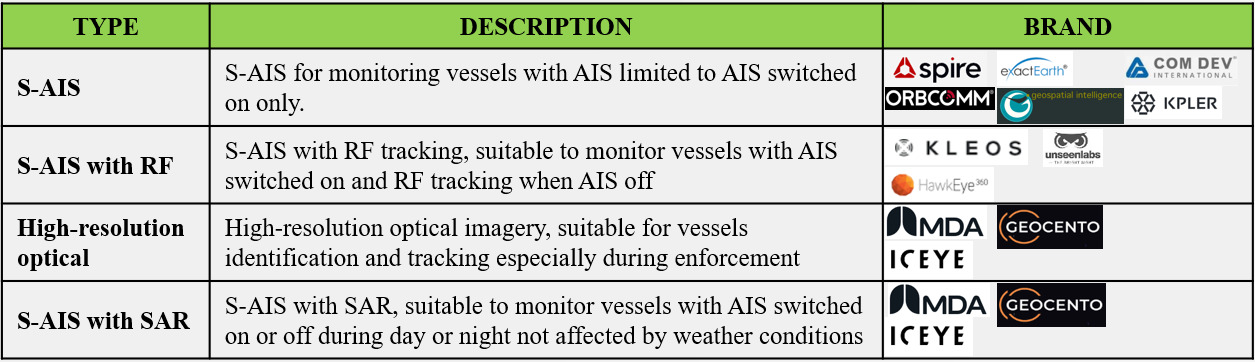

Malaysia has three options for acquiring space-derived maritime surveillance services: (1) subscribing from a commercial provider; (2) acquiring sovereign satellites; and (3) collaborating with other ASEAN members. For short-term and mid-term strategy, subscribing to commercial services is the best option to identify the needs and costs before immediately committing to sovereign capability or collaborating with ASEAN members, which may be better suited to a mid- and long-term strategy. Several types of commercial source space-derived services are suitable for maritime security, including S-AIS, S-AIS with RF tracking, high-resolution optical imagery satellite and S-AIS with SAR sensor. Acquisition of multiple platforms will increase the capability to detect, identify and track during enforcement. The most reliable platforms are the S-AIS with the SAR sensor satellite for dark vessel detection and a high-resolution optical imagery satellite for identification and tracking. Table 1 compares space information for maritime security in the current market.

As for sovereign space capability, the A-SEANSAT-PG 1 is the first Malaysian-made LEO cube satellite launched on 27 June 2023 on a Soyuz-2-1b Fregat vehicle in Russia (Angkasa-X, 2023). The primary function of this satellite is S-AIS, and its secondary function is a high-resolution optical imager sensor for monitoring, search and rescue, and other strategic applications. However, these functions are insufficient to detect dark vessels and owning a satellite with S-AIS and SAR sensors will cost as much as ~USD$28 million (Todd, 2023).

The third option is to collaborate with other ASEAN countries as a long-term strategy that involves aligning needs and understanding of sharing the space information and the satellite’s operating cost. As mentioned in the ASEAN space readiness, space capability still needs time to grow.

From a cost-benefit perspective, space services appear to offer Malaysia a valuable opportunity to improve maritime security, especially IUUF, and help Malaysia do more with less. The acquisition of space information should consider three issues: (1) the cost must be less than the losses of IUUF; (2) this acquisition must be able to enhance the current effectiveness and reduce the operation cost of other surveillance means; and (3) space-derived services will always be a complement to air operation because it has no enforcement capability.

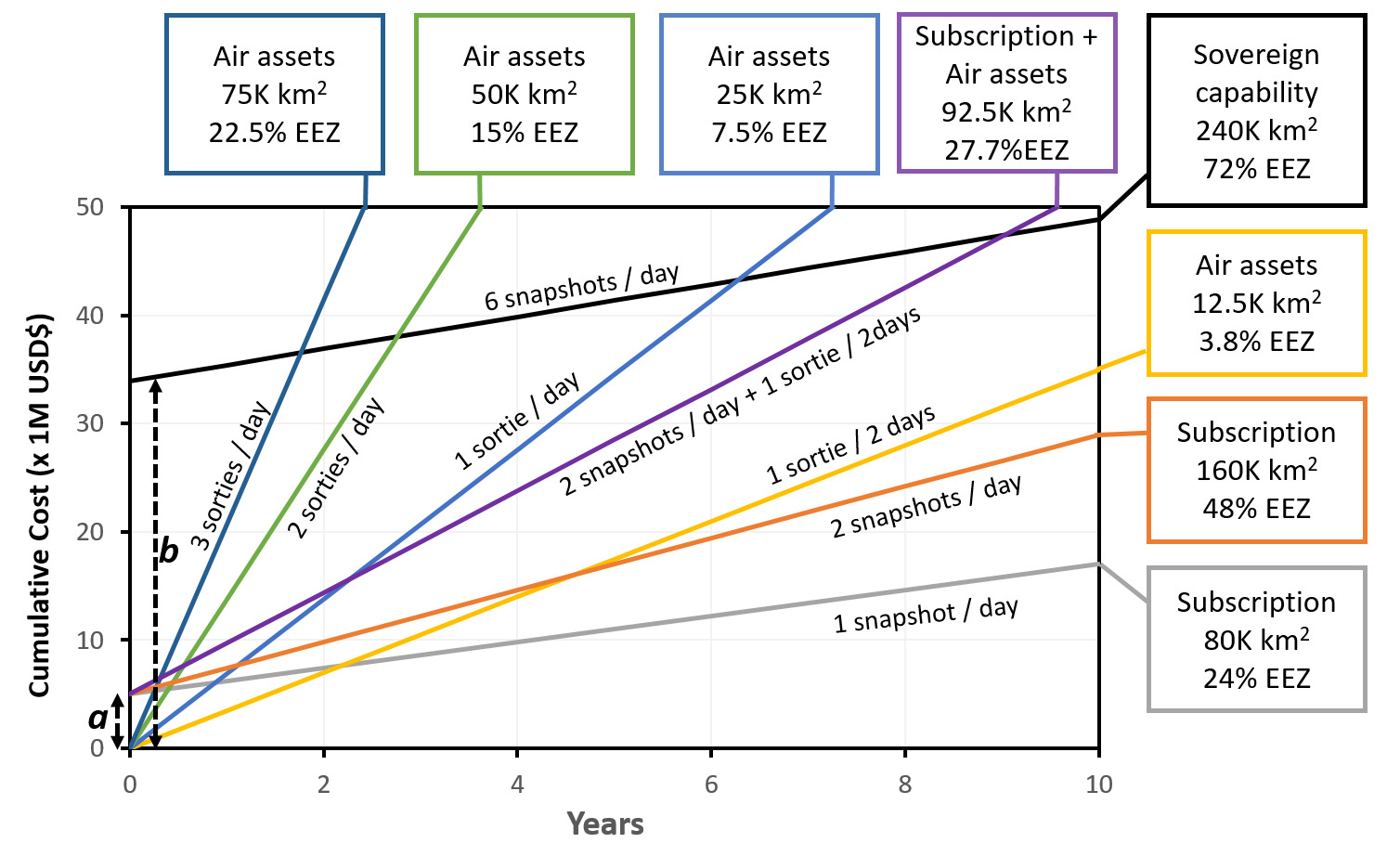

Figure 7 shows the estimated accumulated cost over 10 years comparing the use of: (1) Air assets only; (2) Subscription to a commercial satellite service; and (3) Sovereign space capability. The accumulated costs are calculated based on costing for using aircraft and/or satellites as discussed in Section 5. The estimated cost to cover the EEZ depends on the number of sorties per day with the percentage of EEZ coverage. For example, three sorties per day using air assets will cover an area of ~22.5% of the EEZ. On the other hand, subscription to a commercial SAR satellite service is ~USD$1600 per snapshot for a swath width scan of 200 km x 200 km (Geocento, 2023). The accumulated cost annually will be USD$1.2 million with two snapshots per day and an additional assumption of USD$5 million (see Figure 7 label a) for the initial setup cost for a space command exploitation infrastructure.

For sovereign space capability, the costs are greater but can be cost-effective in the long-term. As mentioned earlier, owning a SAR satellite costs ~USD$28 million; adding on the initial ground control and space services infrastructure setup will cost an overall total of ~USD$35 million (see Figure 7 label b). This amount will burden Malaysia economically and therefore a whole-of-government approach is needed to make sure the capability is not underused. The estimated operational cost of a satellite is ~USD$1.5 million annually (Globalcom, 2019). The sovereign SAR satellite option may be affordable in the next five years as space technology advances and becomes smaller and more accessible (Kulu, 2021; Kwon et al., 2021).

Since the space capability complements air operations, the preferred method is a hybrid of commercial (two snapshots per day) with one sortie per two days, which will cover ~92,500 km2 or 27.7% of the EEZ area. From Figure 7, it will take just over two years to break even with the cost using air assets to do one sortie per day.

The space domain has significant utility in contributing to Malaysian maritime security. The cost of space information has become more affordable than half a decade ago, which makes it an increasingly cost-effective option. Detecting IUUF vessels will become much more manageable and might reduce the significant economic loss. Space information can reduce the costs for the high frequency of air patrol, and aircraft usage can concentrate on tracking the vessels during enforcement. Overall, the space information complements the enforcement operations by air and sea.

5. Incorporating space information in Malaysia’s governance framework

This section will address how space information can be introduced into the Malaysian maritime security framework to complement and enhance existing capabilities. Figure 8 shows how the space services can be integrated into the framework as shown in in Figure 4. The Integrated information phase is where the space domain plays a vital role as it can provide more information. As discussed in Section 4, there are various sources of space services, such as S-AIS, RF, VIIRS, and High-Resolution Optical and SAR satellites. This information can be acquired through three capability options: (1) sovereign satellites; (2) subscription to commercial services; and (3) shared information from partners or allies. Space services will provide complete information on suspected vessels, such as size, colour, location, direction and situation, up to near-real-time (NRT), subject to the satellites’ timing. All this information will be integrated into intelligence reports with advisory actions in countering the maritime threats.

With the space-integrated information, the authorities will have better situational awareness in the Decision phase. In addition to the advantage for decision-makers, this concept can enhance the Action phase by using space information in monitoring and enforcement without necessarily putting any aircraft or vessels on patrol. The space services can reduce the unnecessary search for suspected vessels by timely cueing from the satellite. Thus, it will reduce the required assets for searching and put more effort into tracking in the enforcement operation.

Without space information results in limited accuracy, and the low efficiency may deplete the resources faster. Proper management of space information can maximise the output from the limited resources and reduce the IUUF incidents, reducing government loss. The application of this framework will increase the effectiveness of limited resources by spending less on aircraft and vessels for patrolling. It also provides more extensive coverage with more persistence in detecting and tracking when using more satellites. It also serves as a basis for a regional framework to enhance maritime security, especially when Malaysia has sufficient experience in using space services and products.

To implement space technologies in Malaysia’s governance framework, several steps need to be considered. This reduces development risk and avoids wasting unnecessary resources on redundancy and underusing commercial subscriptions or space technology acquisition. This implementation is not limited to enhancing maritime security but also broader application of national security, as well as other areas such as agriculture, search and rescue, disaster relief and the environment. It also considers how to align national policies and guidance, civilian agencies and ministries’ needs, and regional security needs into short-term, medium-term and long-term planning.

5.1. Sovereign space capability

A sovereign space capability is critical for Malaysia’s national security, independence and environmental monitoring. The sovereign space capability will provide national control over tasking and products, giving a wider usage and better security in space information. However, the sovereign space capability requires a high upfront cost. Thus, the implementation plan of the sovereign aspect is a plan to lead the space domain usage into Malaysia by considering the risks, cost and an estimated timeline for acquiring sovereign space capabilities. Under the sovereign aspect, there are four elements: (1) policy; (2) awareness; (3) process and organisation; and (4) capability. The first element is policy, a predefined course of action that sets the rules for government or organisational strategy and goals. Policy highlights necessary steps and directs decision-makers on addressing problems when they develop (Rethore, 2024). Policies need to be reviewed and revised so the space domain is considered as a distinct focus in supporting Malaysia’s security and interests. The Malaysia Defence White Paper 2020 stated all the domains involved: cyber, air, maritime and land (Ministry of Defence, 2020). Even though the space capability had integrated into all other domains, it did not highlight the importance of the space domain itself. Thus, the recommendation for reviewing the Malaysia Defence White Paper 2020 is to consider space as a specific domain on par with cyber, air, maritime and land domains.

The second element is space domain awareness, which is to develop and implement a space awareness and education framework as part of a whole-of-government approach. Space awareness is essential to gain knowledge of space information usage before Malaysia acquires any space services and sovereign space capability. Malaysia can benefit more if space information is maximised not only by security but by other sectors as well.

The third element is process and organisation, which highlights the actions on how to use the space information. Therefore, in the element of process and organisation, a space information integration framework is required to establish a Joint Space Information Centre (JSIC) with subject matter experts from various agencies to process and disseminate related space information. Capability is the last element of the sovereign aspect, which aims to assess the utility and viability of sovereign space capability to ensure the return on investment is worthwhile.

5.2. Subscription to commercial services

On the other hand, subscribing to commercial services can offer an immediate product through well-established service providers, reducing delivery risk. The first element is engagement, and the second element is exploitation. Section 4 mentions the estimated cost of taking a snap image from a satellite on a one-time demand basis. Thus, engagement in short-term or medium-term subscriptions may get better product and services at a lower cost. The exploitation element is essential to avoid ineffective space information handling and the additional data integration cost when subscribing to different output data formats. Overall, in this commercial aspect, Malaysia as a user must seek suitable space services with affordable prices and the best outcome or result. The estimation of commercial space capabilities subscription is after the action phase.

5.3. Collaboration with ASEAN states

Collaborating amongst ASEAN states leads to shared cost and reduced acquisition risk but requires agreement on capabilities and operations among partners. Collaboration provides a valuable mechanism to enhance ASEAN members’ engagement and spread the potential development risk. Broadly, there are two main issues to focus on: information sharing; and collaboration in acquiring the space capability. It is essential to establish a space information network or implement joint space initiatives like sharing information in TCA (Krishnan, 2022). ASEAN members may have subscribed to a different commercial platform or satellite with different periods, and orbits may enable Malaysia to obtain additional space information. On the capability element, establishing a collaborative framework to consider the sharing in operating space systems is expected to happen only in the latter phase because of the complexity due to government-to-government conflict of interest. Discussion on collaboration space systems will only occur when the ASEAN countries have a similar concept to the European Union.

The maritime security with space information concept pointed out the usage of space-derived services in enhancing the effectiveness of the current concept. The concept involves using more complete data and high persistence in detecting and tracking vessels operating in the EEZ with a more cost-effective method and broader coverage area. At the same time, the implementation phase pointed out the importance of the elements involved in three aspects by considering the risk, cost and process involved. It lays out an approach that identifies who and what to do as a whole-of-government approach in acquiring these space capabilities not only for security issues but also for other issues as well.

6. Conclusion

The maritime environment is vital to Malaysia’s prosperity. However, both traditional and non-traditional threats pose challenges to Malaysia’s sovereignty and economy. This paper has focused on the most costly economic threat, IUUF, and has presented how space-based assets can assist countering this threat. Broadly, the maritime environment in Malaysia is divided into three categories: maritime defence, security and safety. The IUUF problem is under maritime defence and security mainly led by three key government agencies: MMEA, MAF and Police Marine.

To counter IUUF, the operators of modus operandi need to be identified. Most IUUF operators turn off their AIS, manipulate their flags, and/or alter their vessel identification when fishing. IUUF operators also perform transshipment at sea, where smaller fishing vessels transfer their catch to a larger ship for transport and trade elsewhere. Understanding this modus operandi helps shape solutions to detect IUUF activity. Knowing AIS-off hotspots also enables the Department of Fisheries Malaysia to build a database of IUUF activity according to season and location. Identified AIS-off hotspots also allow security agencies and defence forces to focus on selected areas at specific periods of the season instead of the whole EEZ. Addressing IUUF depends on the speed and accuracy of detection, identification and tracking of illegal operators.

Malaysia has actively tightened the national legislation and is highly committed to regional and international regulations and action plans. In the past decade, Malaysia has increased its efforts in maritime surveillance and some operations were performed jointly with Malaysian agencies and other Southeast Asian countries. One of the ongoing joint operations within Malaysia is done under ESSCOM, and there are two multilateral cooperations ongoing: the MSP and the TCA. While these operations have shown positive results, the losses by IUUF have remained high(~USD$1 billion in 2022). In this work, it has been shown that, increasing the rate of effort using the currently available aircraft for daily surveillance of the whole area, EEZ requires an annual budget of ~USD$88 million, which further burdens Malaysia’s budget. Hence, alternative methods are worth exploring in a different domain besides the air and sea domains.

The space-derived services can provide a cost-effective enhancement to Malaysia’s maritime security and fill the gap to address IUUF. The LEO satellite is the most common type of satellite used for maritime surveillance. These satellites can locate, detect and potentially identify vessels operating within the designated coverage area. It provides complete information on the suspected vessel, which will reduce the search time and minimise the asset deployment. There are a few types of sensors used for maritime surveillance: (1) Satellite-AIS (S-AIS) provides broader coverage to detect vessels with AIS; (2) S-AIS with Radio Frequency (RF) for geolocation can detect the radio transmission from the AIS-on and AIS-off vessels; (3) S-AIS with Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) can detect heat signal from the vessel’s lighting during night; (4) S-AIS with Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) can detect an AIS-off vessel in all weather; and (5) S-AIS with high-resolution optical can provide complete information such as the feature and NRT situation of the vessel.

Malaysia has three options to acquire this space information. First, subscription to a commercial service offers an immediate availability through choices of established service providers which reduce delivery risk and will cost ~USD$6.2 million annually with two snaps per day. Second, launching a sovereign satellite requires a high upfront cost but provides national control over tasking and products, which will cost ~USD$35 million to build and launch the satellite, and an operating cost of ~USD$1.5 million yearly. Third, collaborating with other ASEAN states shares the cost and reduces the acquisition risk but requires agreement on capabilities and operations among partners. The first option appeared as the most economical cost to acquire the space information in the short and medium term.

Acquiring information via space capabilities can counter IUUF operations by enhancing vessel detection, identification and tracking. Such space information is complementary to current operations using air and sea assets. The current maritime security framework needs to be embedded with the space information concept to utilise the space-derived services, especially to integrate with other information and assist in monitoring and enforcement by detecting, identifying and tracking the suspected vessels. There are three key capabilities in the implementation phase, which are: sovereign space capability; (2) subscription to a commercial service; and (3) collaboration with ASEAN states. The suggested implementation phase is essential to understand the process, mitigate the risk and estimate the duration required to acquire space-derived services. All in all, the space-derived services can also address other non-traditional threats as well as traditional threats.

Malaysian Maritime Zone (MMZ) refers to both sea and air above Malaysia’s EEZ.

The AIS is a maritime communications device that broadcasts very high frequency (VHF) radio signals to transfer data such as ship information, position, course, speed, planned voyage and characteristics. AIS improves navigation safety and traffic management.

Cost is based on a CA235 aircraft, which is similar to the RMAF CN235. The aircraft cost calculator developed by Sandhills Global (2024) is available by subscribing to https://www.aircraftcostcalculator.com/.

_a_vessel_disabling_its_ais_at_different_time_durations_to_obscure_its_illegal_activiti.png)

_iuuf_incidents_within_asean_(dark_blue)_and_malaysia_(light_blue)._data_compiled_fr.png)

_s-ais___rf._reproduced_with_permission_from_unseenlabs__y_435940_._(b)_s-ais_and_viirs.png)

_a_vessel_disabling_its_ais_at_different_time_durations_to_obscure_its_illegal_activiti.png)

_iuuf_incidents_within_asean_(dark_blue)_and_malaysia_(light_blue)._data_compiled_fr.png)

_s-ais___rf._reproduced_with_permission_from_unseenlabs__y_435940_._(b)_s-ais_and_viirs.png)