1. Introduction

This research formally documents the impact and influence of Australia’s Work Health Safety (WHS) legislation (Work Health and Safety Act (Cth), 2011) on the regulated military aviation community within the Australian Defence Force (ADF). Australia introduced the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (WHSA) in 2011. The Act consists of 276 sections spread over 14 parts. It provides a framework harmonising WHS processes, standards and definitions within state legislations for application to the Commonwealth of Australia. The emphasis on the workplace as a catalyst for hazards and risks is the basis of a duty holder’s safety obligations (Work Health and Safety Act (Cth), 2011).

The WHSA is linked to the Australian Federal Criminal Code Act 1995 (Criminal Code Act (Cth), 1995), allowing offences to be treated as crimes and punished accordingly. The WHSA legal framework includes:

-

regulations that specify in detail the steps required to achieve compliance

-

codes of practice as practical guidance assisting duty holders in meeting the required duty of care obligations outlined in the WHSA

-

guidance material from Comcare.[1]

The duty holders and their duties under the WHSA are:

-

The Person Conducting a Business or Undertaking (PCBU) – The person or organisation that carries the primary duty of care assuring the health and safety of workers under that person or organisation. For the ADF, the PCBU is the Commonwealth. As an entity, it can only act and make decisions through individuals. Therefore, if an individual is working on behalf of the Commonwealth, the Commonwealth is engaged in that task as the PCBU.

-

An officer of the PCBU – A person who makes decisions that affect the business undertaking. In Defence, the officers are limited to the Defence Committee, a group of 16 senior members of the ADF and Department of Defence (DoD). It is the duty of these officers to ensure the PCBU complies with the WHSA duties and, to that end, they must resource and deliver the outcomes of those duties. Officers of the PCBU cannot delegate their duty of care, but in Defence, the chain of command is relied upon to undertake all necessary functions and tasks on the Defence Committee’s behalf.

-

A worker – Anyone lawfully working for the PCBU. Under the WHSA, workers have a duty of care for their own WHS and to ensure that their actions do not adversely affect the WHS of others. This includes complying with the PCBU policy, procedures and instructions that relate to WHS.

Duties are required to be exercised So Far As Is Reasonably Practicable (SFAIRP or SFARP as used in Defence). SFAIRP is an objective test used by the courts to assess retrospectively what could reasonably have been done in any given circumstance. This is an essential concept in the WHSA. If properly applied, it can lead to safer workplaces.

‘Reasonably practicable’ obliges duty holders to consider all relevant matters when discharging their duties, including:

-

the likelihood of hazard realisation

-

the degree of harm associated with the hazard

-

what the duty holder knows about the hazard and the ways of eliminating or minimising the risk of hazard realisation

-

the availability and suitability of ways to eliminate the risk of hazard realisation

-

the cost associated with the available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, including whether the cost is grossly disproportionate to the risk.

When it comes to the management of risk at each level of duty, Section 17 of the WHSA explicitly states that a duty holder must:

-

eliminate risks to WHS SFAIRP

-

minimise risks SFAIRP if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks to WHS.

When elimination is not reasonably practicable, the WHSA mandates that risk minimisation activities follow a Hierarchy of Controls (HoC), as shown in Figure 1, progressing from the most effective controls at the top level to the least effective controls at the bottom level. The duty holder is legally obliged to apply the most effective control available. If not, there must be a clear justification for the use of a less effective control.

The WHSA explicitly states in Section 12D that the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) can declare that certain provisions of the WHSA do not apply to Defence (Australian Defence Force, 2012), in particular:

-

For warlike and non-warlike operations:

-

Section 38 – Duty to notify of notifiable incidents: The nature of military activity (e.g., armed conflict in sensitive and remote locations) means that Section 38 would create a significant reporting obligation on the ADF regarding incidents requiring immediate notification to the Commonwealth. This requirement would place a substantial clerical workload on those already limited by location and available resources.

-

Section 39 – Duty to preserve incident sites: A difficult requirement for the ADF to comply with given incident sites may be in remote international locations near hostile entities.

-

-

For all ADF members at all times:

-

Sections 47–49 – Consultation with workers: The requirement for consultation with ADF members through a formal bargaining framework and nominated WHS representatives from the body of workers is inimical to the discipline of the ADF and the nature of military service.

-

Sections 50–79 – Health and safety representatives and work groups: As above.

-

Sections 84–89 – Right to cease or direct cessation of unsafe work: ADF members do not have the right to cease work where they are concerned about risks to their health and safety.

-

These exemptions were made so that Australia’s defence policy could continue to be self-contained in the direct defence of Australia (Australian Defence Force, 2012). However, Defence has received no such exemption from WHSA Section 17 – Management of risks.

The WHSA Regulations and Codes of Practice cover an array of business undertakings. Figure 2 indicates the work types addressed in the WHSA. Aviation, explosives and radiation are separated because they represent areas of work that are too complex for the WHSA to address with regulations and codes of practice alone.

Due to the unique complexity of Defence aviation, amplification of the statutory WHSA obligations is required to ensure Defence discharges its duties correctly. To achieve this, the ADF established the Defence Aviation Safety Framework (DASF) in 2016 (Australian Defence Force, 2016b), which designates accountability at the appropriate level and is underpinned by the:

-

appointment of a Defence Aviation Authority (Def AA)

-

establishment of a Defence Aviation Safety Authority (DASA)

-

implementation of a Defence Aviation Safety Program (DASP)

-

promulgation of effective Defence Aviation Safety Regulations (DASR)

-

establishment of an independent accident and incident investigative capability.

Figure 3 illustrates the structure of the DASF. Its purpose is to provide a credible and defensible framework that Command can apply within the regulated community. The explicit separation of assure and ensure was a result of the Sea King Board of Inquiry in 2007 (Australian Defence Force, 2007). At that time, there was confusion about who owned operational risk, and it was mandated that the Military Aviation Authority (now DASA) should remain independent of risk decisions. Command is responsible for operating within the bounds of the DASP, using the DASR to ensure the Initial and Continuing Airworthiness of flying assets SFAIRP. The DASF is maintained by DASA, who support Command by assuring that the airworthiness decisions made are congruent with the DASR and are, therefore, credible and defensible under the WHSA. It is the responsibility of the Def AA (an officer of the PCBU) to resource the DASF, enabling flexible and comprehensive safety assurance of Defence aviation operations.

The DASF introduction required a fundamental shift in how military aviation safety was viewed from a WHS perspective. The DASP is based on the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Annex 19 (International Civil Aviation Organization, 2013) and details how Defence aviation safety is ensured through the maintenance of technical and operational airworthiness. The focus of the current paper is limited to the technical airworthiness elements of the DASP.

As shown in Figure 4, understanding of the DASP interaction with the WHSA has evolved to the current view of the DASP being fully enveloped, amplifying the ADF aviation safety statutory WHSA obligations.

An essential element of the DASP is the DASR. The DASR regulates day-to-day Defence aviation activity satisfying the DASP required outcomes, using the concepts of Initial and Continuing Airworthiness lifted from the contemporary European Military Airworthiness Requirements (EMAR). The DASR are a credible and defensible method of aviation safety regulation, embodying the WHSA requirements and internationally recognised standards of practice.

2. Literature Review

2.1. WHS Legislation

Since the enactment of the WHSA in Australia, significant research has been conducted on workplace safety culture and how it impacts an industry’s safety performance (Lingard et al., 2014) and industry compliance with the WHSA (Lingard et al., 2017). One study of WHS culture from 2011 indicated that 77% of personnel in the mining industry do not actively identify hazards and manage risk appropriately in accordance with the industry’s own policies (Bahn, 2012). Such findings indicated workplace obligations associated with the WHSA were not well understood in general, with education identified as a key concern (Bahn & Barratt-Pugh, 2014).

It is broadly accepted that the military workplace is significantly more dangerous than the civil sector, but the idea that high risk is unavoidable and a ‘cost of doing business’ (Turner & Tennant, 2009) is no longer acceptable. Aviation regulation is ‘social regulation’, as it involves protecting the public interest (Stewart, 1994). Over time, the public has become less tolerant of workplace injury or death. Formal safety regulation is necessary for military aviation (Emmerson, 2014) and is subject to the same scrutiny as all industries. The requirement to eliminate or minimise risk SFAIRP is now mandatory across Australia.

2.2. SFAIRP

A considerable amount of research has been conducted to interpret ‘reasonably practicable’ (Sherriff, 2011). Prior to the WHSA, Occupational Health and Safety legislation generated significant debate on what was required of duty holders in the workplace (Bluff & Johnstone, 2005). A point of contention was the test of ‘reasonableness’ and how judges might apply the law to workplace accidents in assessing for negligence (Anderson & Hughes, 2012). Before the WHSA, the industry managed risk to a ‘tolerable level’ (Clothier et al., 2013), termed As Low As Reasonably Practicable (ALARP), where the risk is so low it is not worth the cost to make it any lower (Yasseri, 2013). ‘Reasonableness’ was measured by assessing residual risk against a ‘tolerable level’, as standardised in ISO 31000 (ISO 31000 Risk Management - Guidelines, 2018), regardless of the consequences associated with the risk (Ale et al., 2015; Robinson & Francis, 2014).

In 2014, the Australian Risk Engineering Society determined that the ISO 31000 ALARP principles did not comply with the WHSA, as managing risk to a ‘tolerable level’ was no longer sufficient (Safety Case Guidelines Under the Provisions of the Model Work Health & Safety Act 2011, 2014). This was a position echoed by the rail industry (Robinson & Francis, 2014) and the ADF (DDAAFS, 2014), which was transitioning to a new regulatory framework at the time. It was noted by the ADF that historically, the risk was not being managed correctly to true ALARP but to ‘as low as required by the signing authority’, which, although similar to other military partners, was not in line with the WHSA (Marsh, 2012).

2.3. Military Aviation Regulation

The ADF’s bespoke airworthiness regulations (Adams, 1995) pre-DASR were held in high regard among small- to medium-sized militaries, influencing multiple international partners in the past (Graham, 1995; Pobog-Jaworowski, 1995). As such, the transfer to the EMAR-based DASR has been closely observed and widely publicised (Pittaway, 2016; Slocombe, 2018). The ADF has a history of applying scrutiny to its airworthiness system, with major reviews conducted in 1998 (Weston et al., 1998) and 2007 (Smith, 2007), each driven by catastrophic accidents (Air Power Development Centre, 2013). The evolution of aviation safety in the ADF has been a journey of achieving the right amount of regulation to balance protection with production, ultimately driving down the number of hull losses (bars) and fatalities (dots), as illustrated in Figure 5.

The fatal Nias Island Sea King accident in 2005 brought ADF airworthiness safety management back into focus (Australian Defence Force, 2007) and was a catalyst for the formalisation of the first DASP in 2011 (Australian Defence Force, 2011). The 2011 DASP was state of the art and drew from ISO 31000 and the ICAO Safety Management Manual (International Civil Aviation Organization, 2009), formalising ALARP as the primary ADF risk management tool (Australian Defence Force, 2011). ALARP also became the industry standard for risk management in the EMAR (EDA, 2017) and UK Military Aviation Authority (Yasseri, 2013).

During the formative part of the DASR evolution, the ADF expended considerable effort in assessing whether the 2011 DASP risk management processes were compliant with the WHSA, ultimately concluding that ALARP is not equivalent to SFAIRP (DDAAFS, 2014). This determination had a significant impact on technical airworthiness, with far-reaching implications for the DASP. The ADF is now acutely aware of its obligations under the WHSA. SFAIRP has been embraced, as reflected in all of the newly overhauled ADF WHS policy statements (Australian Defence Force, 2017) and safety manuals (Australian Defence Force, 2019). Although the shift from ALARP to SFAIRP was only one aspect of the greater change experienced with DASR, it was one worthy of further exploration due to its impact on safety and the legal obligations of duty holders in the military.

The legal ramifications of these nuances are now being experienced in the wider Australian aviation industry. A fatal hot air ballooning accident in 2013 in Australia (Work Health Authority v Outback Ballooning Pty Ltd [2019] HCA 2, n.d.) resulted in court action, assigning accountability under the new WHS legislation, specifically citing SFAIRP obligations.[2] To this end, accurately understanding the Australian military air operators’ duties under the WHSA is of the utmost importance.

3. Methodology

To ensure this study yields functional findings, its scope is limited to exploring how Defence, as the PCBU, discharges its WHS obligations through its aviation regulations. The qualitative data used for this study was obtained from a range of documents,[3] as summarised in Table 1, which were reviewed, examined and interpreted in accordance with document analysis guidelines (Bowen, 2009). For this study, it was necessary to sort the relevant documentation into categories; each category was ranked based on release authority and target audience. A higher rank corresponds to a higher release authority and a wider target audience. The study, therefore, used secondary data to investigate the title problem.

Documents were included in this study only if they were confirmed as credible and correct. Documents were determined as credible and correct if they were published, signed or had a record of delivery. Rank 1, 2 and 3 documents took precedence in officially defining the current program and explaining the legislative environment in which Defence operates. Rank 4 and 5 documents were used only to interpret and understand the transition between the old and new safety programs. Since these are not freely available in the public domain, this paper does not depend on them.

Five research objectives were articulated to achieve the aims of this study:

-

Explain why the ADF DASR regulatory framework was introduced (see Section 4.1).

-

Determine which key sections of the WHSA have flowed down into the ADF DASR regulatory framework (see Section 4.2).

-

Ascertain the influence of the WHS legislation on the ADF DASR regulatory framework (see Section 4.3).

-

Capture the main WHS-specific issues experienced by the ADF in transitioning to the DASR (see Section 4.4).

-

Extract the key lessons learnt from the ADF experience for potential adoption by other states, such as New Zealand, with a nascent DASP (New Zealand Defence Force, 2019) (see Section 4.5).

4. Analysis

4.1. The Military Aviation Regulatory Framework of Australia

Before DASF 2016 (introduced to align Defence aviation with the WHSA), the ADF identified that the technical and operational airworthiness frameworks required replacement. As discussed in the literature review, the ADF Technical Airworthiness Regulation (TAREG) was world renowned, but the TAREG was not keeping up with aviation safety international best practice and was considered cumbersome and expensive when introducing new aircraft (Australian Defence Force, 2016c).

The replacement regulatory framework (DASR) was designed as a set of common safety rules and requirements that, if followed, achieved DASP required outcomes. The regulated community (Command) must apply the DASR during operations to ensure Continuing Airworthiness, and the regulator (DASA) must assure the Def AA of their correct application.

EMAR was selected as the basis for the technical elements of the DASR for certain reasons:

-

EMAR was specifically designed to be adopted by nations of varying size and maturity, meaning EMAR is flexible and cost efficient in its application.

-

EMAR is contemporary, internationally recognised and ICAO compliant. As such, it provides greater safety assurance and efficiency than other civil regulatory systems like the US Federal Aviation Regulations and the Australian Civil Aviation Safety Regulations.

-

EMAR enables a seamless interaction with international and regional partners and industry suppliers (military and civil), facilitating the best opportunity for sustainment solutions that exploit global supply chains.

-

EMAR is drafted in plain English for easy translation, is outcome-based (as is the WHSA) and best accommodates the ADF aviation regulation principles.

The following EMAR Initial and Continuing Airworthiness suites appear in the DASR:

-

Part 21: Initial Airworthiness Management (DASR 21)

-

Part M: Continuing Airworthiness Management (DASR M)

-

Part 145: Maintenance Organisations (DASR 145)

-

Part 66: Military Aircraft Maintenance Licencing (DASR 66)

-

Part 147: Military Aircraft Maintenance Training Organisation (DASR 147)

Under DASR, approved technical organisations that perform an ensure function (DASR 21, DASR M and DASR 145) must have an Aviation Safety Management System (ASMS) in place. The ASMS model established under DASR is based on ICAO Annex 19 as the model of international best practice.

4.2. Key Sections of the Australian WHSA

The key sections of the WHS legislation are presented in two tables: duty holder requirements (Table 2) and Safety Risk Management (SRM) (Table 3). Table 2 relates to the statutory WHSA organisational duties and who carries the duty. In Defence, Commanders are the duty holders who must ensure Initial Airworthiness (Sections 22–24 – Acquisition) and Continuing Airworthiness (Sections 19–21 – Management). Command personnel may be required to hold both acquisition- and management-related duties, as per Section 15. The DASF is completely independent of Command, and in the role of assuring safety, personnel in the DASF do not hold any WHSA duties. Comparatively, Table 3 relates to the SRM responsibilities of duty holders under the WHS.

The role of the DASF is purely specialist amplification of WHS provisions for the management of Defence aviation hazards in support of Command. As per Section 14, the duties bestowed upon Command cannot be transferred to the DASF; the double lines in Figure 3 explicitly represent this separation between ensure and assure.

Figure 6 summarises all of the WHSA sections relevant to SRM and illustrates how they are integrated. The remainder of this work focuses on how the SRM-specific sections in Table 3 have influenced aviation safety regulation in Australia, as these sections have the broadest influence on the regulated community.

4.3. WHS Influence on Military Aviation Regulation

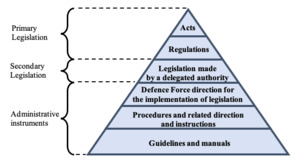

As stated in the introduction, the DASP is an amplification of the WHSA for Defence aviation. The DASR are the rulebook ensuring the safety outcomes of the DASP are achieved. Regarding the hierarchy of document authority, further clarification is provided in Figure 7.

Primary legislation gives legal effect to government policy and communicates the law, principally by Acts of Parliament. Secondary legislation is written law made by an executive authority under the provisions of an Act of Parliament, which allows a named executive to implement and administer the requirements of primary legislation. In the case of the ADF, this named executive is the CDF under Australia’s Defence Act 1903 (Australian Defence Force, 2012).

For the ADF, the CDF Joint Directive 2016 mandating the establishment of a DASF is secondary legislation under the WHSA (Australian Defence Force, 2016b). The DASR plays the role of an administrative instrument under procedures and related directions and instructions. In complying with the DASR, the operator achieves the outcomes laid out in the DASP and is compliant up the chain through the Joint Directive 2016 to the WHSA. The two most significant influences the WHSA has on the DASR, as outlined in Table 2, are:

-

what constitutes a duty holder and what the duties are

-

how risks must be managed in the workplace.

As stated in Section 4.1, SRM is of prime interest in this work as it has a wide and far-reaching impact on the Defence aviation community. SRM is one of the four DASR ASMS Components (Australian Defence Force, 2016a), based on ICAO Annex 19. Logically, the SRM Component cites the WHSA for both of its elements:

-

hazard identification

-

safety risk assessment and mitigation.

4.4. WHS-Specific Issues Encountered by the ADF Transitioning to DASR

The ADF used an incremental spiral transition during the DASR introduction, a ‘test-and-adjust’ model of implementation. This model allowed the ADF to manage any ‘complications’ that arose by engaging with the regulated community to develop solutions and determine the next step (Australian Defence Force, 2016c). Airworthiness SRM underwent a substantial transformation with the establishment of the DASF, requiring some creative solutions during development.

In 2014, before the establishment of the DASF, the ADF shifted the primary SRM philosophy from ISO 31000-based ALARP to WHSA-aligned SFAIRP for all aviation activity (DDAAFS, 2014). As explored in the literature review in Section 2, the ADF, along with multiple other industries, asserted that relying on standards for SRM, like ISO 31000, was non-compliant with the WHSA.

Between the introduction of SFAIRP in 2014 and the release of the DASF in 2016, the ADF was still using the TAREG with the newly mandated SFAIRP approach, seemingly applying it as a ‘bandaid’. This led to confusion among duty holders concerning the meaning of, and obligations associated with, the expression ‘SFAIRP’. The primary issues encountered were:

-

Transition from the Defence version of ALARP to WHSA SFAIRP – Historically, Defence SRM used predetermined acceptable or tolerable levels of risk, or ‘as low as required by the signing authority’. If risks were assessed as high, they could be escalated to a higher authority for acceptance. Although this is not strictly how ALARP should be applied, it is how the Defence application evolved (Marsh, 2012). Once risks were accepted, duty holders would cease risk treatment, irrespective of whether further risk reduction was ‘reasonably practicable’ in that circumstance. Additionally, once risks were accepted, the controls were poorly monitored/reviewed for ongoing effectiveness. Therefore, following the old SRM, duty holders could be led into error under the WHSA, believing they had discharged their obligations when that was not necessarily the case. This was particularly true where the hazard degree of harm was high, but the likelihood was assessed as rare.

-

Applying the WHSA SRM requirements consistently – The WHSA SRM requirements are simple in theory but difficult and complex to apply consistently in practice.

-

Misunderstanding of the WHSA SRM requirements – One of the most common misunderstandings concerns duty holders mandating either risk elimination or minimisation SFAIRP, as opposed to mandating that risk must first be eliminated SFAIRP, and only where elimination is not possible can minimisation controls be utilised.

-

Assessing and capturing when risk elimination is not possible – Under the WHSA, minimisation of risk can only be considered for SRM if the costs associated with elimination are shown to be grossly disproportionate to the risk. Assessing gross disproportionality is complex and cannot follow a standardised approach because every situation is unique; this relies on SRM expertise in the regulated community. Historically, this crucial step was largely ignored, as it was assumed that activities would commence, whatever the associated risk was, and SRM was a risk minimisation tool used to reduce the risk as low as required for it to be acceptable. In reality, elimination is always possible by simply terminating the activity.

-

Determining what is ‘reasonably practicable’ –The point at which the level of care afforded by a duty holder was considered ‘reasonably practicable’ in each circumstance was unclear. This requires an intimate understanding of the WHSA HoC and reasonable knowledge of the availability and suitability of those controls.

As these issues were experienced before the release of the DASR in 2016, the solutions developed in consultation with the regulated community could be written into the DASR. This provided an excellent opportunity for the solutions to be rolled out concurrently with the wider transition to the DASF.

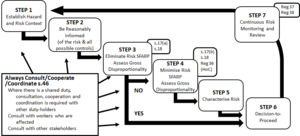

4.5. Key Lessons Learnt by the ADF

To address the issues listed in Section 4.4, the ADF endeavoured to standardise Defence aviation SRM to the greatest extent possible. This was to assist the regulated community in achieving compliance with the WHSA when discharging daily duties under the DASR. This culminated in the development of a seven-step SRM process, as shown in Figure 8, which is included under the element of safety risk assessment and mitigation of the DASR ASMS. The seven-step process is based on the ISO 31000 process but incorporates the WHSA-specific SRM requirements of:

-

Section 17: Risks must be eliminated SFAIRP, and if it is not reasonable to eliminate, risks must be minimised SFAIRP.

-

Section 18: The five elements of how the WHSA defines ‘reasonably practicable’, as listed in Section 1.

-

Section 46: All duty holders must consult, cooperate and coordinate with others who share that same duty.

-

Regulation 36: Hierarchy of risk control measures.

-

Regulation 37: Maintenance of control measures.

-

Regulation 38: Review of control measures.

The strength of the seven-step process is that, if followed correctly, it addresses all five of the issues discussed in Section 4.4:

-

Transition from the Defence version of ALARP to WHSA SFAIRP – The concept of managing risk to a tolerable level is no longer sufficient. Step 2 requires the user to identify all possible controls, and only where elimination is not possible are they able to assess which minimisation controls are ‘reasonably practicable’ for implementation in subsequent Steps 3 and 4.

-

Applying the WHSA SRM requirements consistently – The establishment of a standardised SRM process, included in the DASR ASMS, ensures that SRM is conducted the same way every time and complies with the WHSA.

-

Misunderstanding of the WHSA SRM requirements – Step 3 of elimination cannot be skipped; therefore, the duty holder will always consider elimination before minimisation as per the WHSA. Additionally, Step 6 separates the decision to proceed from Step 3, affording the duty holder another opportunity to eliminate the risk by terminating the activity.

-

Assessing and capturing when risk elimination is not possible – Again, Step 3 ensures that where elimination is not possible, the assessment of gross disproportionality is formally captured before risk minimisation is considered.

-

Determining what is ‘reasonably practicable’ – Steps 3 and 4 refer to Section 18 of the WHSA and guide the user through the SRM strategies enacted to fulfil the WHSA requirements.

To ensure the seven-step process is not left in the safety manual on the shelf, it has been written into all of the SRM-related airworthiness administration tools available to the regulated community:

-

Command Clearance – For issues outside the aircraft Type Certification Basis (TCB), where there is an urgent operational imperative for risk retention.

-

Military Permit to Fly – For issues outside the aircraft TCB, where there is an operational imperative for risk retention.

-

Airworthiness Issue Paper – For significant ongoing issues outside the TCB that may require adjustment of the TCB.

-

Management of Deferred Defects.

-

Unsafe Condition Assessments – Determination if a defect represents a fleet-wide issue outside the TCB.

The strength of writing the seven-step process into the airworthiness tools used by the regulated community is that it ensures the safest possible outcomes in practice, legally safeguarding the duty holder by guiding compliance with the WHSA through the correct application.

5. Discussion

Although there are other means of SRM that are considered Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) to the WHSA, the previously employed method of SRM in Defence by satisfying a standard (ISO 31000) is no longer an AMC. Defence responds well to standardised processes, especially in the technical realm, so although moving to the outcome-based models of DASR and the WHSA is meant to afford duty holders more freedom in discharging their duties, standardising SRM is a sensible and intelligent solution.

It is important that duty holders fully understand their obligations and the correct application of the seven-step process to ensure compliance with the act when conducting SRM. Blindly following the seven-step process could lead to error; intelligent application and critical judgement at each step are still required. To enable effective uptake of the DASF and new SRM, the ADF rolled out mandatory WHS-specific education for the entire technical workforce in Defence aviation.

The influence of the new WHS legislations for SRM, not just for aviation but for the entire Defence Force, can be summarised in a single phrase: ‘Think controls, not risk levels’. This is a safer way to conduct SRM and ensures credible and defensible risk management strategies are in place should a hazard occurrence lead to a reportable event. This is an important factor because if a reportable event ever comes before a court of law under the new WHS legislation, a judge will scrutinise how risks were controlled, not how they were assessed.

6. Conclusion

In many nations, WHS legislation applies to the relevant military regulator, its agencies and the armed forces. This paper provides the first in-depth discussion concerning the far-reaching influence of WHS legislation in Australia and how the military aviation safety regulations have been adjusted to establish compliance with the relevant WHS obligations.

Between 2014 and 2020, ADF aviation underwent significant evolution in the management and assurance of safety. To satisfy the WHSA, enacted in 2011, the fundamental principle at the centre of Defence aviation SRM was changed from ALARP to SFAIRP. This shift heralded the introduction of an overhauled safety framework, the DASF, in 2016. The DASF is underpinned by the safety program (DASP) and a suite of world-class regulations (DASR). The DASR technical airworthiness elements come from the EMAR and include an ICAO-based ASMS. This paper’s research objectives aimed to capitalise on the ADF’s five-year lead time in safety framework implementation to determine any lessons learnt that may be applicable to other states[4] undergoing, or about to undergo, a similar transition.

This paper focused on SRM lessons learnt, specifically surrounding the issues and solutions from the regulated community that came with a change in SRM philosophy, which culminated in a standardised seven-step SRM process now captured in the DASR ASMS. The seven-step process, which was developed in part from ICAO and ISO 31000 standards, is a good example of the wider Defence principle of ‘as civil as possible; as military as necessary’. It has been written into all risk-related ADF airworthiness tools used by the regulated community in carrying out their daily duties, ensuring ongoing high levels of safety and legal compliance. As part of this change, the ADF delivered and is still delivering WHS-specific training to the entire aviation community, emphasising duty holder responsibilities and how risks must be managed. The takeaway from this study is that under the modern WHS legislation of Australia, it is imperative that all ADF duty holders think about controls, not risk levels.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the use of DASA material and data for this research. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors only and do not represent those of the DASA. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.