1. Introduction

Terrorism has challenged regimes and changed the course of history in many countries worldwide. The countries consistently most affected by terrorism are primarily located in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia, with one notable exception: the Philippines.

The Philippines has been plagued by terrorism for around five decades. For most of this time, the terrorist threat was internal. With the recent rise of international Islamist terrorism and specifically the threat posed by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), the Philippines also became affected by international terrorism. In 2017, the impact of terrorism culminated in an ISIS-backed group taking over Marawi, a city in southern Philippines. The extremist attack on Marawi led to five months of fighting and saw the destruction of the city. Through the Battle of Marawi, the Philippine forces—supported by the United States and Australia—succeeded in countering the terrorists and liberating Marawi.

Why has the Philippines featured so prominently and for so long as a target of terrorism? What counterterrorism lessons can be learned from the victory over ISIS in 2017?

To answer these questions, this paper addresses:

-

how terrorism is defined and measured globally

-

the history of terrorism in the Philippines

-

ISIS and the impact of global Islamist terrorism

-

the Battle of Marawi, including observations on the impact of close air support (CAS) from the author’s personal experience

-

maritime security and counterterrorism.

Finally, the paper analyses the Philippines’ experience to identify lessons learned from the counterterrorism operations associated with the liberation of Marawi and the role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

2. Terrorism definition and measurement

There are many ways to define terrorism, but a useful and practical definition is provided by the Global Terrorism Index (GTI), which is a comprehensive annual report analysing the impact of terrorism around the world (Institute for Economics & Peace, 2020). The GTI defines terrorism as:

the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.

This definition identifies that terrorism is not only the physical act of an attack but also the psychological impact it has on a society.

The 2020 GTI examined 163 countries, covering 99.7% of the world’s population, in terms of terrorism’s effect on lives lost, injuries and property damage (Institute for Economics & Peace, 2020). Figure 1 summarises the 2020 GTI ranking of countries impacted by terrorism from 2002 to 2019. The figure shows Afghanistan and Iraq were ranked at the top shortly after the 9/11 attacks in the United States, while Syria rose in rank from 100th position to within the top 10 during the Arab Spring. However, it is important to note that the Philippines is the only South-East Asian country to consistently hover within the GTI top 10 in the 20 years since the start of the Index. From 2002 to 2019, the Philippines ranked 13th to 8th in the GTI and averaging at the 10th position. This is not surprising, particularly given the recent impact of global terrorism through the 2017 ISIS-supported terrorist siege of Marawi in the southern Philippines. However, the Philippines has been featured around the GTI’s top 10 even prior to the rise of ISIS.

Why has the Philippines featured in the top 10 of the GTI for so long? What sets it apart from other South-East Asian countries affected by terrorism? The Philippines has been plagued by terrorism for a long time, and this has shaped the history of the entire country. Moreover, terrorism in the Philippines, and adjacent areas in the region, has longstanding and complex ideological origins that differentiate it from the more recent phenomenon of global terrorism (Banlaoi, 2009). This, in turn, affects counterterrorism measures. The region has unique archipelagic geography bounded by seas and oceans, which makes it easy for terrorists to move about undetected, including cross-border engagement. It is therefore important to understand the ideological origins and the physical aspects of maritime and border security and how they influence terrorism in the region.

3. Terrorism in the Philippines

Local terrorist organisations

The Philippines has been plagued by terrorism for decades and has one of the longest-running insurgencies in the world (Joshi, 2017). The Philippines has a range of religious and ideologically motivated terrorist groups. The Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and its offshoot organisation, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), are both Islamist inspired. They sought an independent state in the south of Mindanao where a majority of Muslims reside. From 1996 to 2018, both groups have been party to peace negotiations and agreements with the Philippine Government that have led to renouncing the use of violence. In 2008, members of the MILF who did not want to be part of the peace process established the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF). The Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) is another Islamist terrorist group that operates in south-west Philippines. It pledged allegiance to ISIS in 2014 and is now officially known as Islamic State–East Asia Province, also referred to as the ASG-IS. While Islamist extremist groups have traditionally focused on the southern Philippines, particularly in Mindanao, the Philippines also faces a longstanding communist insurgency that has seen attacks across the country.

The MNLF, led by Nur Misuari, began fighting a separatist rebellion in 1969 and is one of the world’s pioneering modern Muslim separatist movements. The group has strong links with international terror groups that can be traced back to the Gaddafi regime in Libya and the armed opposition to the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. These links ensured valuable training experience for the MNLF, as well as providing technical, financial and ideological support. During the 1980s, the MNLF sent around 500 members to Afghanistan to undergo military training and join the Mujahideen[1] (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020). After the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989, foreign fighters, including Filipinos from the MNLF, returned home. Meanwhile, the remaining Mujahideen in Afghanistan had disagreements and infighting, with the Taliban eventually emerging as the dominant group.

Abdurajak Abubakar Janjalani was one of the Mujahideen the MNLF sent to Afghanistan. He returned to the Philippines along with other foreign fighters. Meanwhile, negotiations between the MNLF and the Philippine Government had been underway to establish an Autonomous Region in the Philippines’. Disagreement among Janjalani and other leading MNLF members over these negotiations led to the establishment of the ASG in 1991, led by Janjalani (Amadar & Tuttle, 2018). The ASG remains active to date, along with the MNLF and its other splinter group, the MILF, established in 1984 and led by Hashim Salamat (de Lima, 2021), although the MNLF and MILF have both committed to an ongoing peace process. However, the recent rise of global Islamist extremism has continued to affect the Philippines.

Islamic State (IS) and global Islamist terrorism

Extremism in the Philippines has developed in conjunction with other Islamist terrorism-related events across the globe. One of the seminal events in terrorism history—which also triggered the creation of the GTI—is the 9/11 terrorist attack in the United States perpetrated by the al-Qaeda terrorist group in 2001. In response, the United States commenced its Global War on Terror, focused initially on Afghanistan, where the ruling Taliban had been accused of harbouring al-Qaeda. Even though sustained counterterrorism efforts by regional states have contained the threat from al-Qaeda, other extremist groups and networks continue to operate across the region (Schreer & Tan, 2019). In 2003, a United States–led coalition invaded Iraq on assertions that the Iraqi Government was building and stockpiling weapons of mass destruction and providing support for terrorist groups. The Iraq War also became a focus for al-Qaeda sympathisers and terrorist activities.

The Arab Spring (2010–2012) is another seminal period when the uprising of citizens of several Arab countries initiated a series of protests and revolts demanding regime change. It resulted in coup d’etats, large-scale conflicts, insurgency, civil war and breakdown of governments. Terrorist groups also featured in the Arab Spring. Syria was among those countries heavily affected by the protests, resulting in a civil war and prolonged unrest, as shown by its sharp rise in the GTI ranking (Figure 1).

ISIS,[2] or Islamic State (IS), was among the major actors in Syria’s unrest during the Arab Spring. The organisation was founded by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in 1999 (Kemp, 2016). Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announced the establishment of an ISIS caliphate across parts of Iraq and Syria, with himself as the first caliph, in 2014. IS influence reached South-East Asia, where many terrorist groups pledged their allegiance to IS and joined the fight in Syria and Iraq. South-East Asian fighters who joined the fight later returned to their home countries and threatened the stability and security of the region. The rapid rise of the influence of IS across the globe became a major security challenge (Amadar & Tuttle, 2018).

In 2014, at least 63 groups in South-East Asia pledged an oath of allegiance to al-Baghdadi and ISIS. Figure 2 shows atrocities within South-East Asia conducted by IS-affiliated terrorists (Ryacudu, 2018). The threat of violent extremism in South-East Asia since 9/11 has evolved in two distinct phases: the al-Qaeda-centric phase and the IS-centric phase (Ryacudu, 2018). During the al-Qaeda-centric phase, about 400 terrorist fighters from the region headed to Afghanistan and Pakistan, where they gained combat training and experience before returning home. These fighters created Jemaah Salafiyyah in Thailand, Kumpulan Militan Malaysia in Malaysia, Jemaah Islamiyah in Singapore and Indonesia, and, as mentioned above, the ASG in the Philippines. On the other hand, the IS-centric phase saw the emergence of IS-affiliated and associated groups, such as Kumpulan Gagak Hitam and al Kubro Generation in Malaysia, Jamaah Ansharut Daulah in Indonesia, and the Islamic State of Lanao (Maute group) and IS in the Philippines (Banlaoi, 2014a, 2014b).

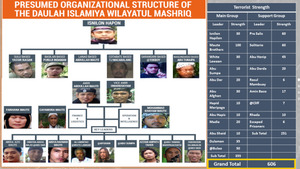

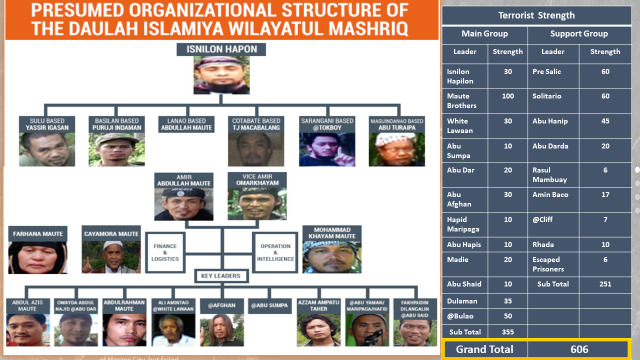

The first step of IS expansion to the Philippines occurred in 2014 when a group of prisoners at Manila’s maximum security prison for high-risk offenders recorded themselves on video swearing allegiance to al-Baghdadi (Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, 2017). One of the prison detainees was Indonesian Saifullah Ibrahim, who became a critical link between Syria, Indonesia and pro-IS groups in Mindanao (Fonbuena, 2017). At the same time, the ASG, now led by Isnilon Hapilon, along with other terrorist groups (BIFF, Ansarul Khilafah Philippines, the Maute group, and the Khalifa Islamiyah Mindanao) also swore allegiance to al-Baghdadi (Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, 2017). The coalition began referring to itself as Islamic State–Eastern Region or the Daulah Islamiyah Wilayatul Mashriq (DIWM) and was endorsed by IS proper through its Shura Council (Amadar & Tuttle, 2018). Figure 3 shows the presumed structure and size of the DIWM led by Hapilon in 2017, based on research by Pamonag (2019) and Banlaoi (2017).

4. The Marawi siege and Battle of Marawi

In May 2017, extremists linked to IS, led by Isnilon Hapilon and the DIWM, laid siege to Marawi City in Lanao Del Sur province in the southern Philippine island of Mindanao. The siege led to the five-month Battle of Marawi between militants and the Philippine Government, which destroyed most of the city (Divinagracia, 2018).

Prior to the siege, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) had been conducting a range of operations against terrorist groups in the remote jungles of the southern Philippines. Throughout 2016, the Maute group and the ASG undertook a series of attacks against Butig and other towns in Lanao Del Sur province.[3] In addition to the local terrorist groups mentioned above, foreign terrorist fighters (FTF) had already been in the country for some time, supporting the Maute group and the ASG (Chalk, 2016). The small city of Butig (population of approximately 22,000) was effectively held by the terrorists for a week. The ambush and siege of Butig and other towns became the training ground for the terrorists prior to the 2017 attack on nearby Marawi.

During the Battle of Marawi, the AFP, the Philippine National Police and the Philippine Forward Air Controllers of the Special Operations Wing of the Philippine Air Force (PAF) constituted the combined land-based forces. The PAF provided the air components responsible for combat support and CAS operations.

By October 2017, the terrorists had been defeated and Marawi City liberated. However, the city was mostly destroyed and its population displaced. The battle resulted in 920 terrorists killed, 165 government forces casualties and 87 civilian casualties (see Figure 4). The number of terrorists killed rose from an initial assessment of 606 to 920 because terrorists were actively recruited during the siege through indoctrination, radicalisation, affinity, monetary enticements and force (Pamonag, 2019).

Close air support missions

Numerous CAS missions were undertaken in Lanao Del Sur in support of the ground troops attacking the terrorist groups. The OV-10 was one of the aircraft the PAF used for CAS and the author was the designated squadron commander and one of the pilots (see Figure 5).

The introduction of CAS in Marawi changed the tide of the battle. CAS allowed for faster and more effective clearing of ground. While Philippine ground troops fought frontline battles against the terrorists in 24/7 operations, PAF aircrew and ground staff supported the operation through CAS missions by day and night as needed. With the maintenance of the aircraft; preparations of the required munitions, fuel and supplies; and other activities, the whole ramp and aerodrome resembled a combat scene from the Vietnam War.

The Battle of Marawi demonstrated many lessons on the effective use of CAS. Constant communication between pilots and ground troops by any possible means is crucial during the flight planning stage so pilots can visualise and assess the situation on the ground. Basic communication equipment, such as radio, and access to satellite images and maps are essential during the operation, especially when pinpointing the location of the terrorists and differentiating them from civilians and friendly troops. Terrorists and their snipers typically occupied houses of innocent civilians for cover, and advancing AFP troops also moved through urban buildings that had been previously occupied by the terrorists. The recent experience of air and land forces working together in the 2016 Lanao Del Sur operations greatly assisted effective working relationships in the Battle of Marawi, while the additional intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) support provided by the Royal Australian Air Force enhanced the air intelligence capability (Agence France-Press, 2017).

5. Terrorism and maritime security

Terrorists have long been able to take advantage of the Philippines’ porous borders and internal transit routes due to the country’s complex and varied maritime environment, combined with its limited and inconsistent maritime and border security. This continues to present a major challenge for Philippine counterterrorism.

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 2178 (2014) on FTFs, which the Philippines endorsed, highlighted that FTFs and transnational organised crime groups target gaps in weak border infrastructure and continue to exploit porous and uncontrolled borders. The resolution calls on nations to take action against this. It notes that terrorists and other criminals use forged and other fraudulent travel documents and visas, or abuse others’ original travel documents, to cross international borders, smuggle people and goods, conduct attacks, provide support and join extremist groups elsewhere.

South-East Asian countries continue to face the problem of identifying FTFs who travel illegally to Syria to join IS and return to their home countries undetected, with invalid, inadequate or non-existent documentation (Yaoren & Ramah, 2020). This demonstrates that verification and identification of suspected FTFs going in and out of their countries needs dedicated attention from ASEAN members.

Philippine-based terrorist groups use people-smuggling routes, particularly to Malaysia and Indonesia, to move themselves, FTFs, weapons and other goods to support their activities. Borders in these archipelagic areas are difficult to patrol and enforce. The Malaysian Borneo state of Sabah and Manado in Indonesia’s North Sulawesi province provide common routes used by the FTFs to enter the Philippines (see Figure 6) (Yusa, 2018). The main Indonesian route starts in Manado and transits through the Sangihe Islands before arriving in the Philippines at General Santos City. Another route from Manado transits through Indonesia’s Talaud Islands before arriving at Davao City in the Philippines. In 2016 and 2017, once in the Philippines, FTFs travelled from either General Santos City or Davao City to Marawi City via land transportation.

Terrorist routes from Malaysia to the Philippines start from either Sandakan eastern district in Sabah or Tawau. Other routes via the Philippine islands of Mapun or Tawi-Tawi travel to Zamboanga City in western Mindanao. From there, FTFs travel to Marawi by either land or sea across the Moro Gulf towards Cotabato City. Another route from Malaysia goes north to the Philippine Palawan Island then Negros Island before heading to Mindanao.

Mindanao became the primary destination for returning South-East Asian FTFs. Since FTFs remain undetected, the increased influx of FTFs could brand the country as a haven for jihadist theatre. The abovementioned routes between Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines were all used to smuggle FTFs, terrorist weapons and other material prior to the Marawi siege and during the Battle of Marawi. These routes continue to be used by FTFs and local extremists.

6. Lessons from Marawi

Countering terrorism

Despite the successful defeat of the terrorists in the Battle of Marawi, Mindanao continues to be a popular and easily accessed destination for FTFs from Europe, the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia. There is an ongoing stalemate between the AFP and the ASG-IS in Patikul, Sulu. However, despite the limited movement imposed by the government in connection with COVID-19 protocols, the ASG-IS faction continues its recruitment efforts (Yaoren & Ramah, 2020).

The ASG-IS has been responsible for several piracy incidents in the Sulu-Celebes Sea. This problem is not unique to the Philippines. Asia had the highest incidence of piracy in the world (Conley & MacNeil, 2018). The crossover between terrorism and crime should alarm governments and inspire a call to action to address the problem. Verification, identification and law enforcement measures are necessary to prevent FTFs and other criminals from transiting through or performing illegal activities in these hotspots.

While the high point of the Battle of Marawi is over, the AFP should not lower its guard down and should continue its focus on Mindanao, including a high level of ISR in the Sulu area. Local government units are well placed to assist the AFP to identify FTFs based on their travel history and other indicators, especially those coming from countries with armed conflict. The challenge is not only to detect FTFs but also to block illegal trafficking routes. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen the legal means and security of sea passageways and maritime borders.

Preventing violent extremism

On behalf of the Department of National Defense, the AFP has been proactive in improving its understanding of radicalisation and how to counter extremist views on the ground. The AFP continues to engage closely with local communities and conduct public forums to discuss the nature of violent extremism and alternatives to violence. The AFP also conducts Community Support Programs and courses to educate participants on radicalism and violent extremism, and to instil cultural sensitivity and diversity awareness. Further, at the international level, the Department of National Defense has been addressing terrorism by sharing the knowledge and experience in cooperative activities and initiatives of the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus Experts’ Working Group on Counterterrorism since its establishment in 2010.

A strong and efficient government is essential for effective management of terrorism. In the case of military officers and soldiers, professionalism, good training and fair promotional processes should also be observed for the armed forces to be effective on the battlefield. Improvement and procurement of necessary hardware and equipment should also be considered to accomplish the mission in the shortest possible time with no casualties on the government side. Such a whole-of-government approach involves all levels of government working towards efficient governance to handle complex issues, such as terrorism and extremism. After the armed conflicts, reconstruction and rebuilding work (such as that underway in Marawi) is aimed at winning the support of the people most affected in a post-conflict situation. Civil-military works should be focused on mitigating the effect of the conflict.

The factors and root causes of terrorism and extremism should be addressed not only by military means but also through government, community and private sectors. Unless all the factors that led to the conflict are dealt with, the same situation may arise again. Atrocities have been happening in neighbouring cities around Marawi, including Basilan, Jolo, Ipil, Pata, Piagapo, Zamboanga and Butig, to name a few. Political and military leadership played important roles in the liberation of Marawi. Terrorism affects all elements of society and, therefore, requires engagement and support from a whole-of-nation perspective to address the problem.

7. Countering terrorism in South-East Asia

Terrorism in the Philippines has existed for decades and is still thriving. The government is yet to address long-held grievances. Basic government services in terrorist strongholds must be addressed, as grievances over them are used to agitate people and gain support. Complex challenges such as these are not unique to the Philippines. Conley and MacNeil (2018) assert:

If you want to learn about Asia’s challenges, a good place to start is looking at the problems faced by the Philippines. The Philippines faces a great many political, economic and social challenges, including the rise of China, ailing governance, a weak rule of law and an ethnic separatist movement that has developed transnational linkages with IS.

The Marawi siege revealed South-East Asia’s lack of preparedness, capability and cooperation in countering terrorism. Terrorism’s scope, breadth and intensity continue to pose a threat to the region’s law enforcement, military and intelligence services. The goal for South-East Asian nations and their close partners, such as Australia, should be to work together to isolate, contain and remove the threat of terrorism (Blaxland et al., 2017; Gunaratna, 2018).

IS and other terrorist organisations will continue to pose a threat to the region. Extremist groups are operationally and ideologically linked and derive support from sections of their vulnerable communities. Around the world, terrorists fight for extremist causes. As seen with Iraq and Syria, conflicts will continue to draw FTFs, and the potential for unrest and assaults in their home nations escalates when FTFs return from hostilities (Australian Government Department of Defence, 2016). Extremists have connections with other extremists—in person, online and through shared extremist ideologies. New recruits can readily establish connections to networks in the Middle East and elsewhere. South-East Asian terrorists can therefore operate across borders and join groups with regional and global agendas (Gunaratna, 2018).

ASEAN approaches to maritime security

The Indo-Pacific is a bastion of global economic activity, geopolitics and security dynamics. The maritime security threat to the region suggests that it would benefit from a comprehensive maritime security agreement to enable cooperation among surrounding countries. Such an agreement could seek to protect the increasing seaborne activity, maintain sea lines of communication (SLOCs) and stabilise the region. While a full maritime security agreement may not be likely in the near future, ASEAN could progress a regional agreement focused on a vital part of the Indo-Pacific.

ASEAN members occupy a crucial geopolitical position across the vital sea routes between the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean to the west, and the South and East China Seas to the Pacific Ocean. Over one-third of the world’s seaborne trade passes through South-East Asian waters, including about 80% of China and Japan’s oil imports (Dibb, 2016). According to Dibb (2016):

from a strategic perspective there is great value in having a common ASEAN position and objectives. Collectively the ASEAN group of countries exercise formidable strategic advantage.

Tertia and Perwita (2018) suggest that:

the aims of maritime security are also to protect the Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs), either for trade, harvesting natural sea resources, and other sea-based activities. Thus beyond traditional notion, maritime security addresses the strategy in managing maritime economy or blue economy.

Other regional countries, such as Japan, Australia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Pakistan, are also increasing their maritime reach to secure the SLOCs and exploit more resources. The region also faces the emergence of non-traditional threats in the sea, such as piracy, maritime terrorism, illegal trafficking and environmental degradation. The many maritime security issues have shaped the security dynamics in the Indo-Pacific region (Tertia & Perwita, 2018). The most common non-traditional maritime threat is piracy. As noted above, this crosses into terrorism, with groups such as the ASG-IS pirating cargo ships in the Sulu Sea and abducting hostages (Tertia & Perwita, 2018).

The maritime attacks by the ASG-IS in early 2016 obliged Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines to strengthen security cooperation in the Sulu-Celebes Sea. On 5 May 2016, the foreign ministers and chiefs of defence of the three countries met in Indonesia and issued a joint declaration in which they agreed to intensify naval patrols and strengthen communication and information exchange. This confirmed that the Malacca Strait Patrol would be used as a model for coordinated naval patrols, combined air patrols and exchange of information and intelligence.

The Trilateral Maritime Patrol was formally launched on 19 June 2017 (Storey, 2018). The improved communication and information exchange between the navy commands of the three countries is the most important contribution to addressing maritime security in the Sulu-Celebes Sea. Maritime Command Centers have been established in Tarakan, Kalimantan, Tawau, Sabah, Bongao and Tawi-Tawi. While the naval patrols are important, the piracy–terrorism nexus in the Sulu-Celebes Sea requires not only increased cooperation among the navies of the three countries but also improved inter-agency cooperation within and between each nation (Storey, 2018).

ASEAN approaches to countering violent extremism

The Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia each have a long history of programs to counter violent extremism and are attempting to address it through non-kinetic and preventative efforts (Clamor, 2018).

The need for cooperation on counterterrorism was first identified in the ASEAN Declaration on Transnational Crime (ASEAN, 1997). In November 2002, the Southeast Asia Regional Centre for Counter-Terrorism in Malaysia was established with the overarching purpose of strengthening regional and international cooperation and capacity.

The Trilateral Cooperation Arrangement among Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines includes joint maritime patrols in the Celebes Sea to resolve maritime security lapses, counter the spread of violent extremism and monitor the movement of people. The arrangement could also address related issues like piracy, drug and human trafficking. In addition to combined patrols and operations, intelligence sharing and combined training should also be regularly conducted to strengthen the relationship and improve the execution of the agreement.

Extremism and terrorism were a particular focus of discussions at ASEAN forums in 2017, including the 31st ASEAN Summit held in Manila in November 2017, a month after the Battle of Marawi. The 11th ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime, held just prior to the Summit, endorsed the Manila Declaration to Counter the Rise of Radicalisation and Violent Extremism and updated the ASEAN Comprehensive Plan of Action on Counter Terrorism (ASEAN, 2017). Through the Manila Declaration, ASEAN sought to:

counter radicalisation and violent extremism, in particular those which lead to terrorism in all forms and manifestations, through the prevention of radicalization, financing, recruitment, and mobilization of individuals into terrorist groups (ASEAN, 2017).

The focused discussion on extremism and radicalisation signals that ASEAN member states take terrorism seriously and wish to counter violent extremism. Such engagement is essential to counterterrorism in South-East Asia, but success relies on the commitment of ASEAN member states to take action.

8. Conclusion

The Philippines has a history of terrorism that goes back around 50 years, and the GTI has consistently ranked it in the top 10 countries most affected by terrorism. However, the nature of terrorist groups and their networks has changed. The Philippines’ experience of terrorism demonstrates that no country can deal with terrorism on its own and that the global threat of terrorism continues even when domestic terrorism matters may appear resolved. It also shows that maritime security affects terrorism and other threats for South-East Asian states, particularly those that are archipelagic, like the Philippines.

The Philippines still needs the support and assistance of other countries to prevent and counter terrorism and address ongoing problems with maritime and border security. Strengthening regional maritime and border security with the cooperation of other countries is necessary to address vulnerabilities that are being exploited by terrorists and other criminals. The Philippines and the rest of the region must be vigilant with IS and affiliated militant groups, as their destructive ideology remains, along with the potential for future violent activity.

Solving terrorism requires bringing terrorists and their supporters to justice and punishing them according to the law. Where possible, terrorists should be deradicalised and reintegrated into society as productive citizens. The ultimate goal is to remove the elements that enable terrorism to thrive. As the case of the Philippines has shown, this involves working closely with international partners—including ASEAN and other close partners like Australia—collaboration across agencies, effective maritime and border security, education and support for those citizens most affected, and addressing underlying grievances.

Mujahideen is an Arabic term that refers to people engaged in jihad or the fight on behalf of God.

Also known as Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL).

Butig, Lanao Del Sur, is located 40 km south of Marawi (PhilAtlas, 2018).

_using_the_gti_2020_scoring_.png)

_(map_data__2023_google).png)

_missions_during_the_battle_of_marawi_(map_data__2023_google).png)

___238987_.png)

_using_the_gti_2020_scoring_.png)

_(map_data__2023_google).png)

_missions_during_the_battle_of_marawi_(map_data__2023_google).png)

___238987_.png)