1. Introduction

This isn’t about the military having a ‘green’ view of the world: it’s about the [Australian Defence Force] ADF being well placed to deal with the potential disruptive forces of climate change. (Press et al., 2013, p. 32)

Australia’s security context is deteriorating, the risk of military miscalculation has increased, and Australia could conceivably be drawn into a state-on-state conflict (Australian Government Department of Defence, 2020a, p. 6; Marles, 2022b). As a result, the Australian Government is funding the ADF to become a more capable and lethal force, and the ADF’s cooperation with security partners is deepening (Nicholson, 2022). The ADF is focused on traditional sources of security threats such as great power competition, regional military modernisation, expanding global cyber capabilities and a weakening rules-based global order (Australian Government Department of Defence, 2020a, p. 5). The governments of Australia’s security partners are focusing on similar security issues but also increasingly acknowledging climate change as a critical security element (Australian Security Leaders Climate Group, 2021, p. 2; Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2022, p. v; Climate Council, 2021, p. 1). Climate change has the potential to permanently alter geopolitical environments and catalyse significant direct and indirect security threats (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2022, p. v). Australia and the ADF, however, have been hesitant to prepare for the influence of climate change on security (Australian Security Leaders Climate Group, 2021, p. 2; Expert Group of the International Military Council on Climate and Security, 2020, p. 27).

Defining climate change’s potential effects on Australia’s strategic environment has been the subject of increasing attention in public security discourse and a government national assessment is currently ongoing (Australian Government Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee, 2018; Australian Security Leaders Climate Group, 2021; Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2022; Marles, 2022a; Sargeant, 2021). Most academic reports and national security community analyses focus on national strategic-level security challenges, while there is limited published work on the specific challenges climate change may present to militaries (Palazzo, 2022, p. 4). The available work indicates that climate change’s effects will likely be pervasive across all the ADF’s activities and the Australian security environment. However, the ADF has only limited awareness of the extent of the disruption and military challenges that climate change may create.

This paper expounds potential challenges for the ADF stemming from a changing climate intersecting with Australia’s physical and geopolitical environment. By defining and understanding these challenges, the ADF will be better positioned to determine the actions needed to protect its ability to generate and apply military power. First, the climate–security nexus is outlined to provide a foundation for identification of the ADF’s likely climate-related challenges. Second, the first-order effects of climate change, such as increased extreme climate events and a changing operating environment, are explored from an Australian perspective. This demonstrates that first-order climate change effects will likely cause force structure, capacity and capability challenges for the ADF. Finally, the possible second-order effects of climate change are outlined and contextualised to Australia’s security environment. The resulting challenges for the ADF outlined here highlight the pervasive and disruptive effects of climate change across all the ADF’s activities.

2. Effects of climate change

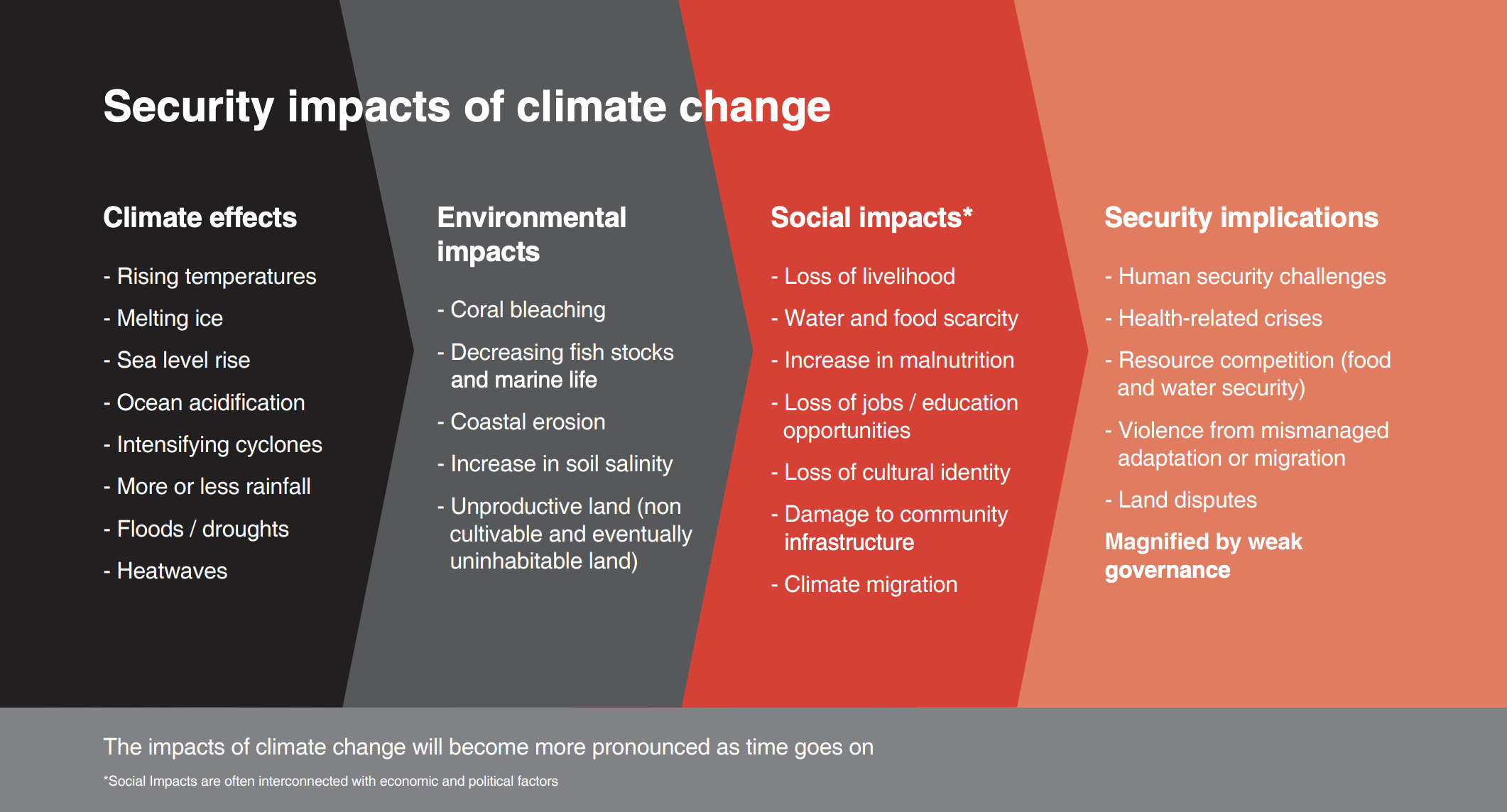

The effects of climate change on security are a fundamental premise for this paper and are broadly established in the literature and recognised by Australia’s closest security partners. New Zealand summarised the security implications of climate change, as shown in Figure 1. Essentially, climate change effects lead to environmental impacts, and environmental impacts create social impacts, which lead to security implications. Australia’s Five Eyes intelligence partners are the United States, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Canada. As liberal democracies with similar national security interests to Australia, they are among Australia’s closest security partners and may share similar geopolitical challenges and security considerations (Leuprecht & McNorton, 2021, p. 5). These countries all recognise the climate–security nexus and, as a result, have comprehensively integrated climate change into their security policies. In what has been described as the securitisation of climate change, the militaries of Australia’s security partners have accepted and emphasised the link between climate change and security to drive climate change action and reduce climate-related security risks (Thomas, 2016, p. 281). For example, the United States security community began to recognise the climate–security nexus in 2007, stating that climate change ‘posed a serious threat to America’s national security’ (CNA Corporation, 2007, p. 3). The United States Department of Defense considers the security implications of climate change risks in its strategy, planning, programming and processes (Biden, 2021).

In contrast, while Australia recognises the climate–security nexus, it has not comprehensively integrated climate change into its defence policy. Climate change has been considered in Australian strategic defence policy since 2009, yet it is generally treated as a singular offshore threat rather than a factor that can alter the strategic environment and affect all ADF activities (Sargeant, 2021, p. 6). One result of this limited emphasis on environmental security is that the potential challenges for the ADF resulting from the first- and second-order effects of climate change have not yet been clearly identified. There is minimal published work globally on the types of challenges climate change will present to militaries, and this limitation extends to the ADF (Palazzo, 2022, p. 4). For the ADF, the most comprehensive summary of the military challenges of climate change is Press et al.'s (2013) report. However, since that report was published, Australia’s security environment has degraded and additional data on climate change have become available.

3. Militaries as first responders

As a security threat, climate change presents militaries, including the ADF, with significant first- and second-order challenges. Perhaps the most visible first-order challenge for militaries is the potential for increasing emergency first responder taskings to provide surge capacity to government responses to extreme climate events (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2022, p. 18; Expert Group of the International Military Council on Climate and Security, 2021, p. 7; Layton, 2021, p. 53). Extreme climate events are increasing in frequency and intensity and often represent a military challenge in the form of supporting government responses. (Expert Group of the International Military Council on Climate and Security, 2021, p. 7). Military taskings in response to extreme climate events extend from the immediately demonstrable use of militaries following fires, floods and cyclones to intervention in human security events enabled by climatic extremes such as drought and disease transmissibility (Pörtner et al., 2022, pp. 7, 10). Militaries are useful in providing first responder assistance because of their contributable capabilities to emergency responses, including planning, intelligence, surveillance, logistics, medical support, airlift and labour (Campbell et al., 2007, p. 86).

Global trends indicate an increasing reliance on militaries as first responders to extreme climate events (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2022, p. 75; Expert Group of the International Military Council on Climate and Security, 2021, p. 7; Scott & Khan, 2016, p. 85). There is a longstanding history of the ADF’s involvement in humanitarian aid/disaster relief (HADR) taskings in addition to its primary warfighting role (Greet, 2008). However, ADF taskings appear to be departing from historical norms as the ADF is experiencing record demand for support in the form of domestic disaster relief operations (Heanue, 2020; Layton, 2021, p. 53). Increasing ADF involvement as an emergency first responder may put pressure on ADF capacity. The challenge for the ADF is to meet emergency first responder role expansion expectations without decreasing its readiness for traditional warfighting roles. The recent record demand for ADF support in domestic disaster relief operations (Dutton & Littleproud, 2021; Heanue, 2020; Layton, 2021, p. 53) is not unexpected when considered in light of Australia’s recent experience of increased extreme climate events such as heat waves, fire danger, sea level rise, intense storms, drought and cyclones (Cai et al., 2018). However, the extent of the demand on the ADF in comparison to historical norms has not been defined in prior published studies and is unknown.

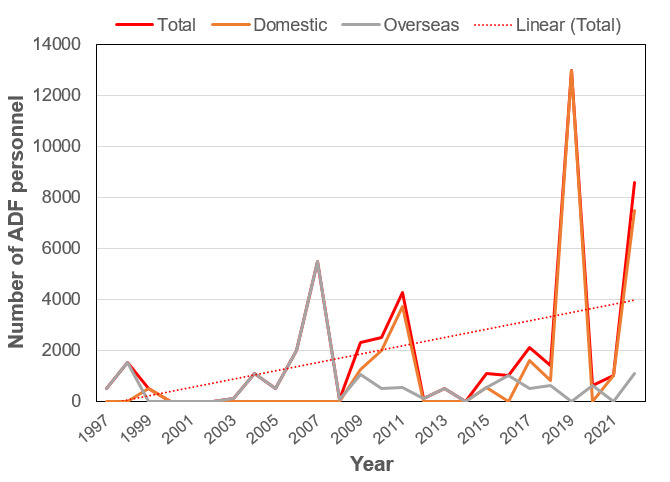

The extent and increasing trend of the ADF’s emergency first response taskings can be quantified. By conducting a historical analysis of open-source data, three key observations can be made regarding an ADF tasking trend. First, as shown in Figure 2, the ADF is experiencing increased numbers of emergency events that it is requested to respond to. Second, Figure 3 shows that the annual commitment of ADF personnel to emergency responses is increasing. Of particular note is that the number of ADF personnel deployed for domestic emergency responses has, in recent years, frequently far exceeded the number deployed overseas. Overseas ADF deployments could increase in frequency and scale as the Australian Government seeks to maintain stability in the event of regional governments being overwhelmed by compounding and concurrent extreme climate events. Third, Figure 4 shows that the increase in ADF emergency response taskings aligns with climate change warming trends, which, over the past 25 years, have consistently resulted in mean temperatures above the long-term average.

4. Changing operating environment

In addition to increased tasking requirements for the ADF, another first-order impact of climate change is physical changes to the operating environment. The climates that militaries are operating in are changing, and this will likely inhibit personnel, equipment and infrastructure’s ability to deliver capability (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2022, p. 76; Expert Group of the International Military Council on Climate and Security, 2021, p. 7). Future environmental conditions will likely present challenges for the ADF to overcome, regardless of its eventual role in responding to extreme climate events. Climate change brings not only an increase in mean global temperature but also an increase in temperature variability. ADF operating environments will regularly feature extreme heat, cold, and other extreme climate events (Scott & Khan, 2016, p. 83). A harsher operating environment may challenge the performance of ADF personnel, equipment and infrastructure.

To maintain current operational capability and seek a strategic advantage, the ADF will need to account for a harsher future operating environment in its force design and sustainment decisions. For example, extreme temperatures may reduce the operating performance of some capabilities. Aircraft engines, for example, may exhibit reduced performance as extreme heat becomes more commonplace in operating locations (M. E. McRae, 2019; Scott & Khan, 2016, p. 83). The mechanism for this reduced performance may be an elevated density altitude, resulting in less dense air at a particular altitude (M. McRae et al., 2021, p. 39). Aircraft will generate less thrust and less lift as the density altitude increases. The effects on equipment may have secondary implications for infrastructure; for example, some airfields may be too short for supporting aircraft at full payloads due to reduced aircraft engine performance in extreme heat conditions. The changing environment may lead the ADF to consider changes to mission profiles, procurement of new equipment or upgrading of infrastructure, further increasing budget pressures.

In addition to the direct or first-order effects of climate change, the second-order effects might pose significant challenges to the ADF. A commonly discussed second-order effect of climate change is its role as a ‘threat multiplier’ of existing vulnerabilities within the traditional security environment. Climate change is expected to result in urgent security threats through its complex interactions with existing security vulnerabilities (Australian Security Leaders Climate Group, 2021, p. 2; Expert Group of the International Military Council on Climate and Security, 2021, p. 7; Fetzek & Mazo, 2014, p. 163). In the extreme, climate change as a threat multiplier has been linked to conflict as an indirect causal factor (Ide et al., 2020; Koubi, 2018, p. 200; von Uexkull & Buhaug, 2021, p. 4). A more likely situation is climate change increasing the risk of governments’ ability to cope with the administrative and financial burdens of extreme climate events being overwhelmed, ultimately threatening state stability (Fetzek & Mazo, 2014, p. 163).

5. Australia’s neighbours

Australia considers the Indo-Pacific region’s stability as important to its security; an unstable state provides an opportunity for an external power to gain a strategic influence in that state (Australian Government Department of Defence, 2016, pp. 69, 127; Dinnen, 2017). Assessment of Australia’s near region identifies an increased risk of regional instability due to climate hazards’ effects on vulnerable states (Glasser, 2021, p. 2), thereby posing a challenge for the ADF. Based on historical trends, it is likely that managing the risk of a hostile power establishing a regional strategic presence close to Australia will entail the ADF being used in a whole-of-government effort to stabilise and develop regional security (Australian Government Department of Defence, 2016, p. 74; Papua New Guinea-Australia Comprehensive Strategic and Economic Partnership, 2020). The ADF’s role in East Timor in 1999 is an example of ADF intervention to stabilise the security environment, deliver humanitarian assistance and promote regional stability (Greet, 2008, p. 45). Papua New Guinea (PNG) is an example of an Australian near-region state at risk of instability due to climate change (Alijahbana et al., 2019, pp. 20–24).

PNG is threatened by the threat multiplier effects of climate change and may need international intervention, potentially by the ADF, to maintain its stability. PNG is in a fragile economic position and already assessed at risk of loan default, including to China (Fetzek & McGinn, 2020; O’Dowd, 2021, p. 400; Wall, 2020). The future cost to PNG of climate-related disasters has been estimated as, on average, 4% of GDP annually, yet these costs will be experienced as a series of economic shocks (Akhtar et al., 2017, p. pp. v–vi; Alijahbana et al., 2020, p. iii). Annual costs will vary depending on climate change events experienced in that year. An economic shock of this magnitude, alongside climate adaptation costs, could threaten PNG’s economy and state stability (Asian Development Bank, 2013, pp. 71–74). Following similar-sized economic shocks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, PNG experienced severe financial stress, requiring Australian and International Monetary Fund assistance to service its debts (International Monetary Fund, 2020; Laveil & Sum, 2020). Continued pressure on the PNG Government from compounding natural disasters increases the risk of state failure or widespread civil unrest (Alijahbana et al., 2019, pp. 20–24). Should these occur, the ADF would likely be tasked by the Australian Government to assist with stabilisation. Potential capacity issues for the ADF emerge when considering that climate change is likely to affect multiple states within the Indo-Pacific region concurrently, meaning several stabilisation tasks may need to occur simultaneously.

Climate change’s second-order effects may also exacerbate or provide new avenues for great power competition. Great powers may seek to use the changing physical environment to achieve strategic advantages. One concern is that China will capitalise on HADR delivery to grow its influence (Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2022, p. 81). Increased influence may lead to host country approval for Chinese military bases within Australia’s immediate region, particularly in the South West Pacific. A People’s Liberation Army base in the South West Pacific would be directly contrary to Australia’s national interests. The China–Solomon Islands security agreement, signed in April 2022, has put the security concerns of a Chinese military base in the Australian security community spotlight (“Really Concerning,” 2022; Roggeveen, 2022).

The various state actions following the January 2022 volcanic eruption in Tonga exemplify climate change’s potential to exacerbate great power competition. After the eruption, commentary began to emerge surrounding an unofficial race to provide aid. Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd called out this race, tweeting that Australia must be first to assist Tonga and, ‘failing that…China will be there in spades’ (Field, 2022). Ultimately, China beat Australia and proudly announced that its emergency aid was the first to arrive (China’s Emergency Aid, 2022). Despite this, Australia’s contribution to Tonga was probably more meaningful through its ongoing coordination of international disaster relief efforts. However, China’s regional assistance capabilities may improve, and its force structure has the capacity to cope with concurrent events. To meet this challenge, the ADF will need appropriate disaster relief capabilities and the capacity to deploy them at short notice without overwhelming itself. As extreme climate events may occur without warning, the potential for short-notice and unplanned HADR taskings decreases the ADF’s ability to take on other taskings during a lower tempo period and reduces opportunities to train for conflict. Capacity pressure may affect force readiness activities, such as the training required to enable the ADF to use military force.

6. Compounding climate-related events

Concurrent and compounding climate-related events present capacity challenges for the ADF. Compound events may create significant food and water security risks. For example, floods, fire and salinity variation can all cause food shortages, and the interaction of multiple climate events of different types can cause increased food security impacts, potentially leading to conflict (Palazzo, 2022, p. 51). Concurrent threats refer to simultaneous, geographically separated extreme climate events that stretch governments’ capacity to respond. Concurrent events are more likely as extreme climate events increase in frequency and intensity. The ADF experienced the challenge of concurrent events in the 2019/20 summer: the ADF undertook simultaneous, large-scale operations in response to a one-in-500-year flooding event in north Queensland (January/February 2019), Tropical Cyclone Trevor in the Northern Territory (March 2019) and east coast bushfires of unprecedented scale (June 2019 – May 2020) (Australian Government Department of Defence, 2019, 2020b). The ADF has demonstrated its capacity to absorb singular large tasks in responding to extreme climate events. However, concurrent events may stretch the ADF’s capacity and capability to respond (Glasser, 2021, p. 2). More regular large-scale deployment of the ADF for domestic and regional emergency assistance tasks may also diminish the ADF’s readiness for warfighting by interrupting training.

A final potential second-order effect of climate change on security is the risk of the unknown. Climate conditions have shifted so far from historical measures that they are now considered novel in the time of human existence (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021, para. A2, pp. 8–9; Perkins-Kirkpatrick et al., 2016). Novel global climatic conditions may interact with the security environment and translate to new security risks. With limited relevant historical data to assist with prediction, new risks might arise in unpredictable ways (Australian Government Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee, 2018, p. 18; Expert Group of the International Military Council on Climate and Security, 2020, p. 5). A rapidly changing climate may drive conflict or instability, requiring the ADF to respond with military force (Palazzo, 2022, p. 52). The ADF might also be called upon to assist the federal government in broader types of tasking. One potential novel security risk is the migration of people displaced by the effects of climate change. The IPCC predicts extensive climate change displacement in developing countries, including those in Australia’s immediate region (Pörtner et al., 2022, p. 15). The realisation of this could result in the Australian Government tasking the ADF to provide surge capacity to the Australian Border Force to protect Australia’s borders. Novel situations are challenging to prepare for and will require the ADF to have the ability to pivot to meet new requirements.

By considering the first- and second-order effects of climate change and contextualising them to Australia’s environment and geopolitical circumstances, it is apparent that the ADF’s capacity, capability and budget will likely face new challenges. Climate-related challenges are visible now in the form of extreme climate events. Current trends indicate the ADF is departing from its historical norms in delivering emergency first response. As the global climate warms, the ADF is experiencing emergency first responder taskings of increasing frequency and magnitude, domestically and internationally. Other first-order effects of a changing climate are expected to result in a more challenging operating environment that may affect the performance of equipment, personnel and infrastructure. The second-order effects of climate change could also lead to significant military challenges for the ADF. Climate change as a threat multiplier is expected to result in increased regional instability, potentially requiring ADF intervention. Climate change has also begun to provide a new vector for great power competition within Australia’s region through the exploitation of extreme climate events as an opportunity to increase regional influence. Concurrent and compounding extreme climate events or novel climate challenges may also challenge the ADF.

7. Conclusion

The resultant capacity and capability challenges for the ADF are not exclusive to climate change threats. Capacity and capability pressures in preparing for security threats are standard considerations in developing any military strategy—a relationship between ends and the ways and means to achieve them (Cerami & Holcomb, 2001, p. 11). However, the ADF’s current approach of omitting climate change’s potential influence across the future security environment means the ADF is attempting to manage climate-related challenges within its existing force. The ADF risks failing to make the necessary force structure, capacity and capability changes to meet future climate-related challenges. Determining the significance of climate risks to the ADF’s operational abilities requires a detailed risk analysis beyond the scope of this paper. In lieu of a risk assessment, a logical deduction is that comprehensively including climate change–induced security considerations in the ADF’s strategic calculus would enable appropriate risk mitigation to be initiated. Force structure changes could bolster the ADF’s capacity and capability to respond to security threats in a security environment affected by climate change.

_and_over.png)

_and_over.png)